The notion that poor children need extra support at school in the form of social services is becoming less novel.

In 2014, the community surrounding Wheatley Middle School gathered to discuss how transforming the middle school into a “community school” might meet those needs on the East Side, as other schools have done in similar communities across the country.

A community school brings social supports — delivered by local businesses and nonprofits — onto the school campus. This concept, which had yet to be tried in San Antonio, provides additional stability for students by supporting their parents and neighbors as well. Because it is based on the needs and resources of the community, every community school looks different.

Three years ago, over the course of three community meetings, San Antonio Independent School District hired the urban planning firm Concordia to shepherd the conversation toward a list of goals and priorities.

The Concordia meetings produced a lot of lists of needs, Wheatley Community School director Tava Herring says, but not a lot of understanding. It’s taken three years to properly set community expectations because the process got entangled in the politics of East Side nonprofits.

“There was a fundamental misunderstanding of what community schools are,” Herring said.

In 2015, the Every Student Succeeds Act, signed by President Barack Obama, replaced the test-heavy No Child Left Behind Act of the George W. Bush administration. While ESSA still allows for high stakes testing, states must also consider additional indicators of student performance and learning. The bill also contains provisions for student supports and initiatives like community schools. In 2015, the U.S. Department of Education awarded $6 million in Full Service Community School Program grants to 12 organizations in 10 states.

The families and students served by community schools in Baltimore, Austin and Oakland have seen major gains in health and educational attainment. With a strategy this adaptable and effective, Herring says, she is determined to see Wheatley Community School succeed despite early challenges and tremendous neighborhood change.

Oakland Unified School District currently has 35 community schools. It will continue to add these services to each of its campuses until the entire district is covered. The expansion is part of a strategic plan that began in 2009 when former Superintendent Anthony Smith began his tenure in Oakland with a year-long listening tour.

In Oakland, community school coordinators are district employees who participate in the Professional Learning Community that allows them to share data and strategies. In addition to the district’s $2.5 million Full-Service Community School Grant, services are funded by state and local funds for after-school activities and mental health, respectively.

The district ended up with fewer nonprofit and business partners than they might have without the public funding. The ones they have meet specific needs that are highly aligned with a specific community school mission.

The focus was not so much getting more partners, but on creating the best learning environment for students, said Andrea Bustamante, Oakland Unified executive director of community school student services.

A study by Stanford University’s Gardner Center surveyed students and parents, and found that the community school environment had improved their relationship to the school, and improved the learning environment.

The East Side is layered in nonprofits, each with their own mission, Herring says. Many are small and in need of financial support, and some saw the Wheatley Community School and its $2.2 million Full Service Community School Grant as a potential revenue stream.

The East Side has seen programs and funds come and go, said Herring, who previously led another nonprofit in the area. Few stick around to do the “deep, dirty, messy” work, she said. Because of this, community members (including those who lead nonprofits) view most services, including Wheatley Community School, as transactional. They have been conditioned to get what they can while they can.

Hoping to win contracts with the school to fund their own programs, each nonprofit offered something valuable, but Herring determined many of these services to be outside the scope of the Wheatley Community School mission.

Herring is not one to allow mission creep, and does not feel obligated to contract with nonprofits that have been left behind by other funders in the past.

“My five-year grant is not going to change 100 years of what happened here,” Herring said.

Even some of its earliest partners have at times made it difficult for Wheatley Community School to establish a distinct presence. The federally-established Eastside Promise Neighborhood and Alamo Colleges’ Eastside Education Training Center are both listed by the community school as partners, yet are tasked with demonstrating their own impact to stakeholders. Both are focused on student success. In that space, what should be cooperation can feel like competition, Herring said.

Citing East Side politics, Wheatley Community School director Tava Herring says it’s taken three years for the school to get on track. Bekah McNeel / Folo Media

“It was supposed to be an ‘everybody together’ thing,” she said, “but it isn’t always.”

A representative from the Eastside Education Training Center identified two potential areas of overlap — GED and English classes — and says the staff is not familiar enough with the community school to comment on how to improve the partnership.

EPN advisory council member Akeem Brown said the misunderstanding and miscommunication about the community school’s mission had impaired cooperation with EPN in the beginning. Now, he says, leadership at both EPN and the Community School have a better understanding of where their missions can complement one another. “We have the chance to get this right,” Brown said.

Whatever misunderstanding there might have been was further complicated by monumental changes in the neighborhood, said EPN spokesperson Mary Ellen Burns. When the San Antonio Housing Authority redeveloped Wheatley Courts, which sat adjacent to Wheatley Middle School, to become the multi-income East Meadows apartments, the majority of the Wheatley Courts residents relocated. The community that had participated in the planning of the Wheatley Community School was no longer living next door.

In light of those realities, Herring and the Wheatley Community School has seen the most progress in its service to adults. It’s actually a great place to start, she says.

During the Concordia sessions in 2014, the community tied the needs of students to the needs of the adults around them. Parents needed jobs and access to healthcare. Many wanted to improve their language skills, complete a GED, and become more financially literate.

So far, Herring has been able to deliver many of those services. The Communities in Schools of San Antonio team at Wheatley Community School effectively reaches into the neighborhoods to let adults know what resources are available. These services and partnerships are stable, Herring said, and more and more people are utilizing them. “If the money left tomorrow, most of our partners would still be here,” Herring said.

Becky Moore is one of those adults who has embraced the community school. She comes to campus regularly, often for hours at a time, and serves on the Wheatley Community School leadership council.

As a member of the community, Moore has been able to identify needs that might not fit into any nonprofit organization’s mission, but make a vital difference to her neighbors.

Once a month Moore hosts a “motivation group” for women in the neighborhood. Originally, she thought she wanted to host a support group for those with terminal illnesses. Then, she says, she realized that there was an even broader need to support women who “have to keep living in this world.”

Speaking Spanish, the women share their frustrations and struggles. Many are single mothers, some are recent immigrants, some fight depression. They bring gifts to encourage those who are grieving. Some ask for advice, others offer it as they share a potluck meal, play Bingo, and take part in other planned activities.

The group had been meeting in one member’s home, Moore says, but as friends brought friends, and more women were attracted to the safe and uplifting space, they outgrew the living room. The classroom at Wheatley is the perfect size for 10 women and their potluck lunch.

SAISD allotted one wing of Wheatley Middle School to house the services provided by the Community School partnerships. While she’s not handing out grant-funded contracts for programming, Herring is ready to offer space to anyone who wants to activate it. CPS and Select Federal Credit Union have used the space for classes and community outreach. Google Fiber helped Herring set up a computer lab to accommodate the wide variety of digital and communications needs.

This is a great start, Herring says, but not an end. Now she wants to see more student supports.

In 2012, University of Maryland School of Social Work received a $500,00 Promise Grant from the U.S. Department of Education, the same grant that created San Antonio’s Eastside Promise Neighborhood. It used the funds to set up community schools in five schools in Baltimore’s Upton/Druid Heights neighborhood. Together the schools are now known as Promise Heights.

Upton/Druid Heights was made famous in the wake of the uprisings following the death of Freddie Gray while in police custody. Coverage highlighted the longstanding issues of unemployment and limited opportunity, with the average neighborhood family living on about $625 per month, and unemployment exceeding 60 percent. The average life expectancy in the neighborhoods is 68 years.

For those who care to look, community school director Henriette Taylor says, the pride and resilience of these storied neighborhoods shines through. The community has what it needs to thrive, so the key is to connect needs and resources. Schools, Taylor said, are natural places to bring everyone together, and the Promise Heights community school coordinators can “triage” issues efficiently.

“We are clearing the path for children who have economic challenges. So when they come into the classroom they have a full belly, they had a place to sleep,” Taylor said.

Infant mortality rates have fallen dramatically thanks to parenting and prenatal education programs. Promise Heights reported no infant deaths (down from a citywide 13.5 per 1,000 in 2009) and a 96 percent full term delivery rate for participants in the B’More for Healthy Babies program, more than eight points higher than the Baltimore city rate. Meanwhile, kinder-readiness and high school graduation rates have increased through academic supports and mentoring.

When SAISD placed the community school on Wheatley’s campus, the middle school was still following the traditional instruction model. The principal at the time was wary of the Community School, fearing it would take away from core academics if kids began spending time on enrichment. The district did little to help the relationship.

“[Test] scores were king,” Herring said.

In 2015, the district hired Pedro Martinez as superintendent. Martinez’s plan for the district includes a heavy push for diversification and innovative school models. For the 2017 school year, SAISD dissolved Wheatley Middle School and, with the support of the community, moved Young Men’s Leadership Academy, an all-boys specialized school, onto the campus. Wheatley Middle School students who did not choose to go to YMLA — those Wheatley Community School was designed to serve — transferred to other nearby middle schools.

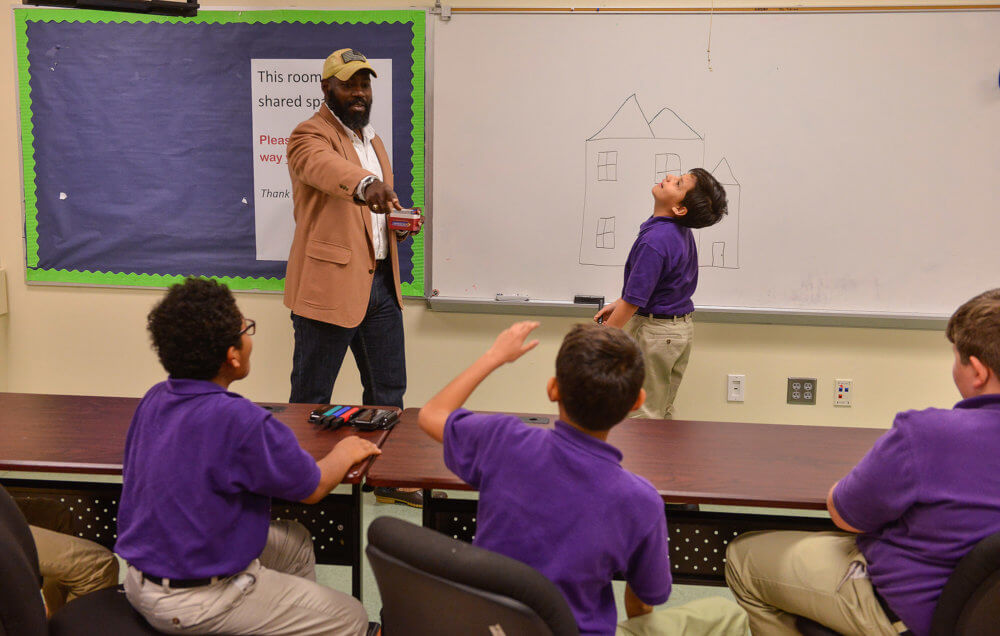

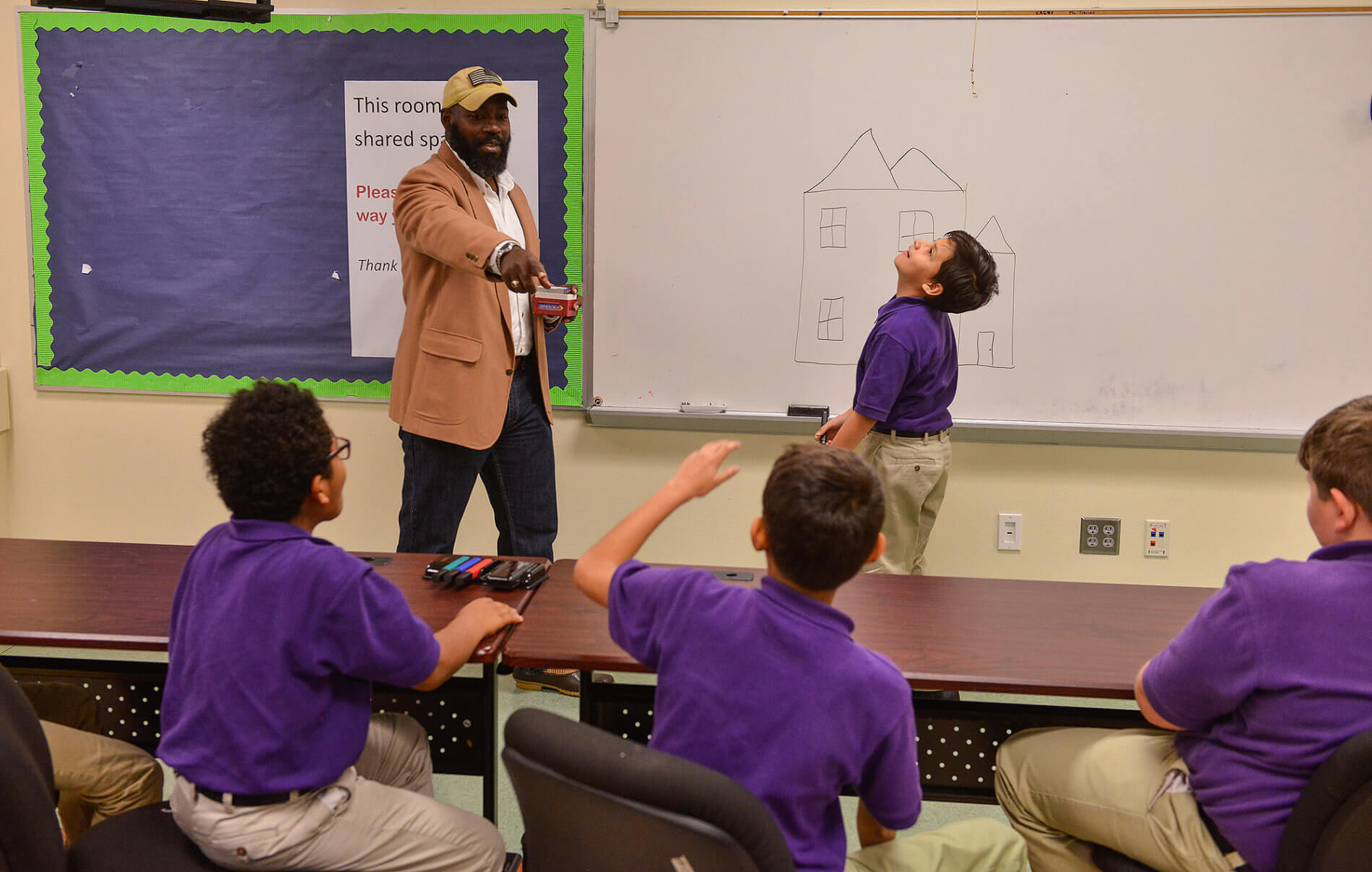

Young Men’s Leadership Academy principal Derrick Brown has been more cooperative with Wheatley Community School, which is still housed on campus. YMLA students have begun serving in the community school, mostly in the Google Fiber community computer lab, as part of their leadership and project-based learning curriculum.

Character development also plays a large role in the YMLA model.

The Omega Psi Phi fraternity, an East Side service organization known as the “Omega Men,” uses one of the rooms in the Wheatley Community School wing to offer small group mentorship to YMLA students identified by YMLA teachers and staff as needing male role models.

For D.J. O’Bryan, 12, the mentorship has reënforced values important to his mom: “trustworthiness” and “respect.”

“I’m glad (my mentor) is a man though,” O’Bryan said. “I think they can help me more than another girl (like mom).”

The other male role model in O’Bryan’s life, his step-father, is in prison. The preteen boy can outline the details of his stepfather’s case, and the racial prejudice at play. His step-father is Hispanic, he explains, and received 25-year prison sentence for a DUI “in a town where they don’t like people who aren’t white.” He explains the racial politics with certainty, a heavy burden for such a young man.

His Omega mentors, black men with a long history in the community, are no strangers to issues of race and identity. They are able to help O’Bryan think through the injustice he feels for his step-dad and focus on his own development.

While mentorship and project-based learning have been good for students, the community school is still underutilized, because the students it was designed to reach are no longer on campus.

YMLA is an open enrollment school, meaning that students can enroll from outside the school’s neighborhood attendance zone on the East Side. Middle class families have been attracted to the single-gender environment, and the campus now has a more socioeconomically diverse population than it did when it was Wheatley Middle School. The need for social services is not as widespread as it had been when the community school was conceived, Herring said.

Those adults receiving services at Wheatley may not be the parents to the students on campus, but they are the parents, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and role models for students somewhere. For the Wheatley Community School to have maximum effect, Herring would like to connect the two.

In Texas, Austin Independent School District has experienced success with community schools as a “turnaround” strategy for two of its lowest performing schools. Webb Middle School and Reagan High School were on the brink of closure when they began to follow the community school philosophy in 2010, an effort spearheaded by Allen Weeks and the Austin Voices for Education and Youth.

In February 2016, a report by Popular Democracy highlighted the gains of the two Austin schools. Webb is now one of the highest performing middle schools in Austin ISD, with growing enrollment and graduation rates. Reagan’s student success indicators are climbing at a similar rate. Childcare and prenatal services at Reagan have yielded a 100 percent graduation rate among teen parents.

In some education reform circles, rigorous curriculum is pitted against wraparound services as the key to turning around a struggling school. At Webb and Reagan, social services and rigorous curriculum go hand-in-hand.

The schools have identified the barriers that keep students from enrolling in rigorous coursework, and addressed them. With basic needs met, the students could focus on school work. School designers selected a curriculum with high payoff that immediately addressed one of the community priorities: getting students in and through college. Reagan has partnered with Austin Community College to adopt an Early College model, so that students can graduate high school with college credit.

Setting it straight: East Meadows was created by a San Antonio Housing Authority initiative.

This article was originally published by the H.E. Butt Foundation’s Folo Media initiative in 2017.