Many want to remember a Rev. King who gave only one speech — with only one line.

Twelve years, three months and 30 days.

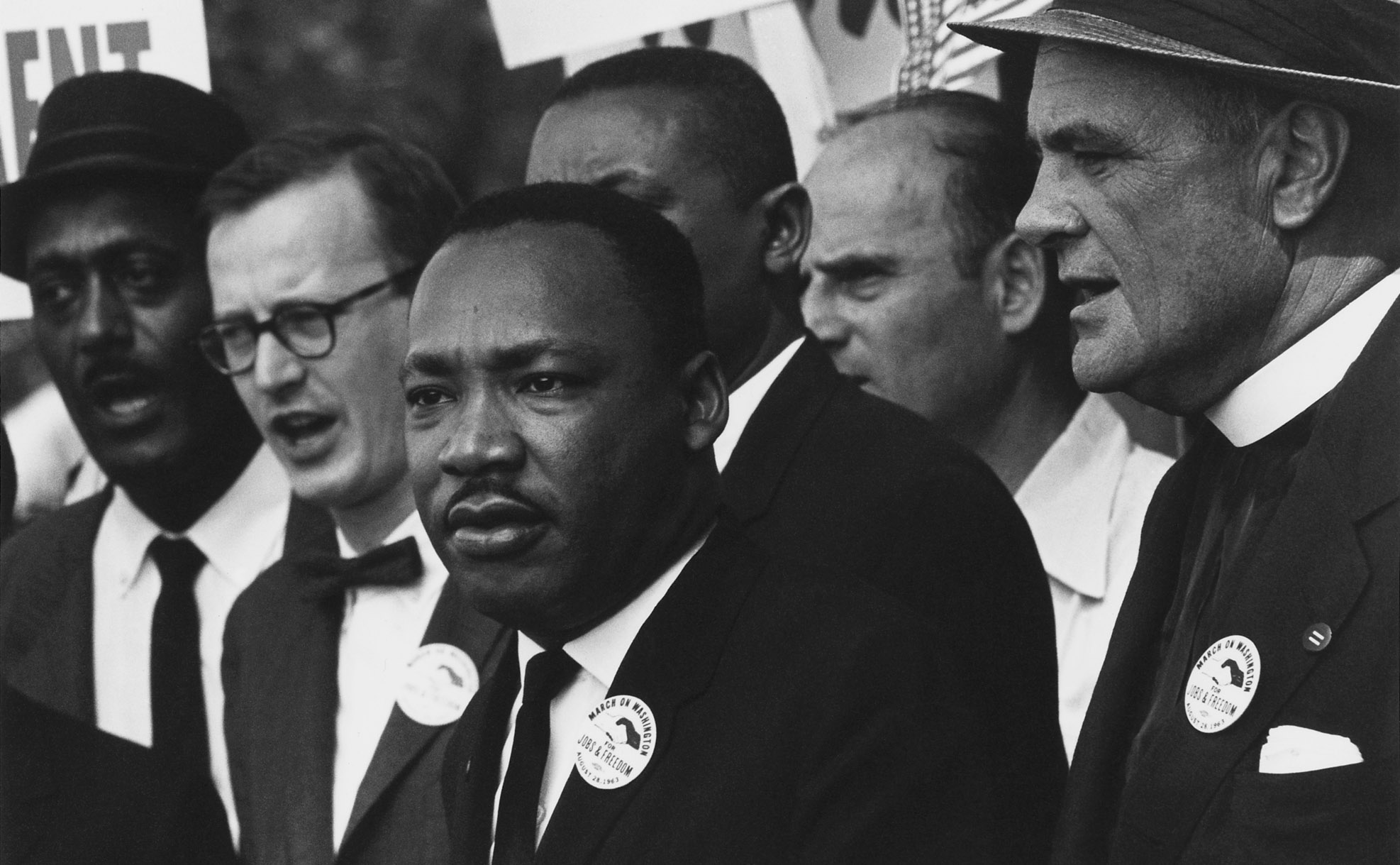

That was the length of Martin Luther King Jr.’s public life.

From Montgomery to Memphis. From boycott to balcony.

Twelve years, three months and 30 days.

During that time, this drum major for justice wielded the baton of nonviolence in leading a parade of conscience through the streets of America and the contours of her soul, challenging the nation to be true to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence and Constitution and faithful to the Judeo-Christian heritage it claimed.

Today, on what would have been his 89th birthday, we will again honor him with a national holiday, and celebrate his life and work. San Antonio will, again, have the largest MLK march in the country.

But which Martin Luther King Jr. will we celebrate? There is a comfortable Martin Luther King Jr. and there is a challenging Martin Luther King Jr.

The comfortable Martin Luther King Jr. gave only one speech in his life, and we’re required to quote one line from that one speech.

The comfortable Martin Luther King Jr. is non-threatening and asks nothing from us.

The comfortable Martin Luther King Jr. is so loved by everyone that his name is invoked to justify any position, no matter how dubious or un-King-like — and often by quoting the one line from the one speech he gave.

The challenging Martin Luther King Jr. was a relentless critic of American foreign policy, racism and an economic system which left so many destitute.

The challenging Martin Luther King Jr. says, yes, speak truth to power, but we must also speak truth to our allies and not go along with them if it means abandoning our principles.

The challenging Martin Luther King Jr. insists that it’s through the discipline of nonviolence that we end the cycles of hatred and violence.

The challenging Martin Luther King Jr. makes us uncomfortable in our complacency and asks that we live out the courage of our convictions.

The comfortable King has a dream. The challenging King knows the dream has yet to be realized and much work is still to be done.

The comfortable King is the one we celebrate at the expense of the challenging King.

In a 1964 Gallup poll, King had a positive rating of 43 percent and a negative rating of 39 percent. In 1966, the last year they polled King’s popularity, his positive was down to 32 percent and his negative up to 63 percent.

For his increasingly frequent and impassioned attacks on poverty and the Vietnam War — and for the Poor People’s Campaign he was planning — he was scorned, even from allies in the Civil Rights Movement.

Yet he persisted. Depressed and isolated, he refused to segregate his moral concerns or mute the trumpet of his voice.

On the 100th anniversary of the birth of the scholar W.E.B. Du Bois, King said, “We cannot talk of Dr. Du Bois without recognizing that he was a radical all of his life.”

The same can be said of King. And from his words, we have a good idea of where he’d stand today on certain issues.

A man who said, “Because I believe that the Father is deeply concerned especially for his suffering and helpless and outcast children, I come tonight to speak for them,” would today be speaking for uninsured children and the disabled and he’d be speaking for the Salvadorans, the Haitians, the Africans.

A man who titled one of his speeches, “A Time to Break Silence,” would raise his voice in support of women who are breaking their silences about sexual harassment and assault.

A young man, who, in 1963, shared his dream for the only country he’d known as his home, would, in 2018, be standing with a new generation of young Dreamers fighting to stay in the only country which they’ve known as their home.

A man who led the march from Selma to Montgomery, which led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, would be opposing the weakening of that law and fighting acts of voter suppression.

In his last speech on the last night of his life, King said, “Now I know we’ve got some difficult days ahead.”

Fifty years later, we are in difficult days with more to come. Difficult days are part of life, including the life of a nation. But difficult days are meant to be overcome.

We celebrate King’s birthday in recognition of the progress he helped bring and as a reminder that we must continue his work.

If we accept his challenge, if we turn a moment into a movement and, through real acts of love, transform chaos into community, we can one day say, as King once said, “We’re not where we ought to be but, thank God, we’re not where we used to be!”

Cary Clack is a San Antonio writer currently working on a book for Trinity University Press called “Dreaming US: Where Did We Go From There?”

This article was originally published by the H.E. Butt Foundation’s Folo Media initiative in 2017.