Evie Garrett has a mission—a clearer mission than most high school freshmen. But she came to it the hard way.

In 2016 Garrett developed a serious bone infection. Numerous surgeries, frightening developments, and a relapse kept her in the hospital for most of the summer, with nurses as her main source of company. The hospital gave her a teddy bear donated by local students through a nonprofit—a rare moment of cheer in a scary time.

Garrett left that summer with a scar on her calf: a reminder to her entire family of the close call and how much they have to be grateful for.

Every time he sees it, her father Bubba Garrett says, “It brings tears to my eyes.”

Evie Garrett knew she wanted to help kids who, like her, were spending a long stretch of childhood hooked up to monitors and IVs, surrounded by more beeping and intercoms than laughter. But she was a shy kid.

Two years after the infection, she visited the Canyon on an overnight retreat with her school, B. T. Wilson 6th Grade School in Kerrville ISD. There something happened, a quirky twist in her unique origin story.

The shy 12-year-old put on a monster onesie, danced, and sang in front of all her peers. Specifically, she sang a song about ticks to the tune of Baby Shark.

“I was just really confident. I was never that confident before,” Garrett said.

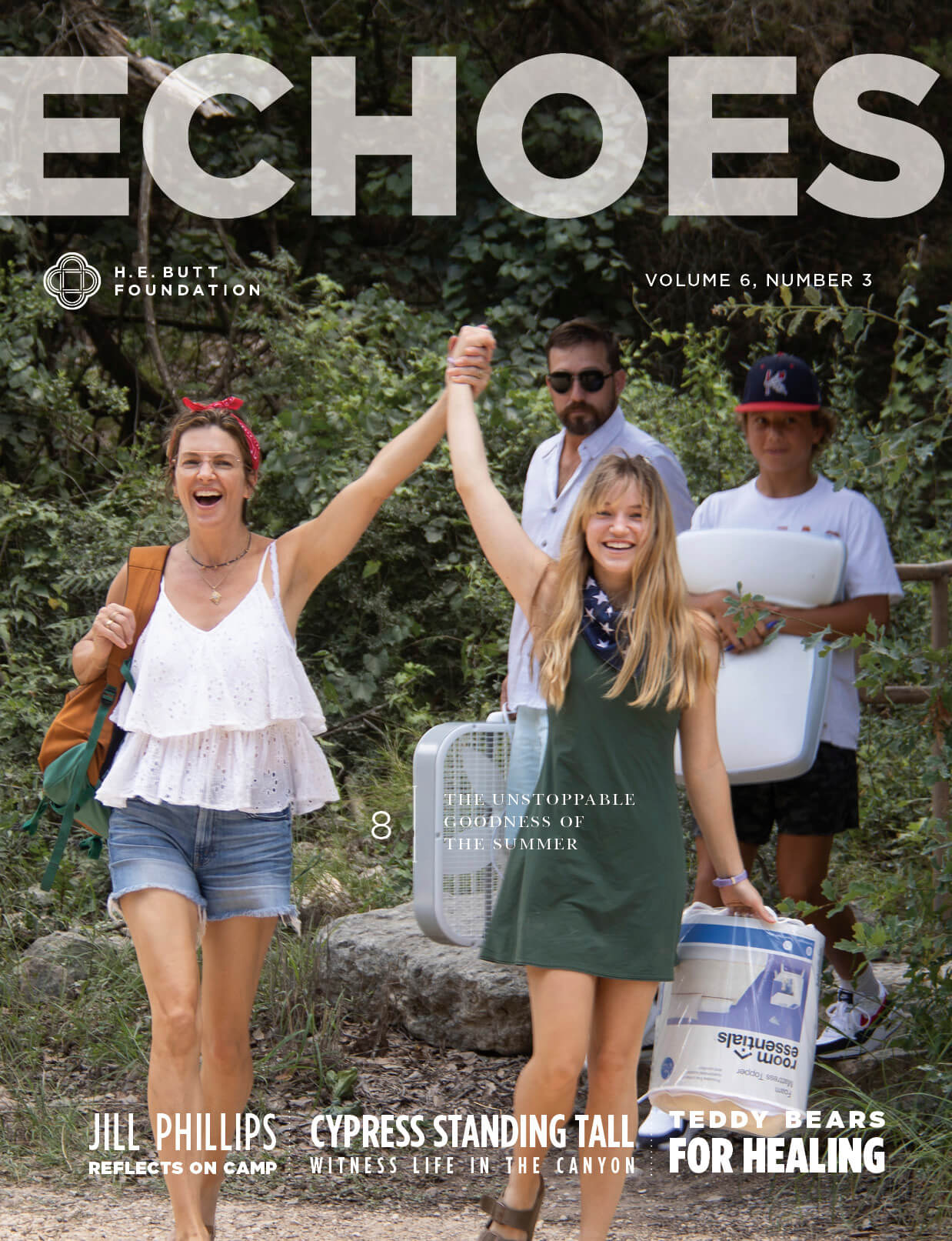

Something changed for her that night. She was ready to put her mission into action.

She thought back to the teddy bear, the one from the local students. It was, she thought, the perfect way to pay forward the comfort and encouragement she had received. To raise money, however, would mean pitching her idea to church groups, civic clubs, and individual donors. It would mean speaking confidently to adults and strangers.

If she could sing a silly song in her pajamas in front of her middle school peers … she could do that.

Evie’s Bears for Boo Boos is now in its fourth year and distributes between 800 and 900 stuffed bears to children in hospitals each year.

“She’s just always attacking life, out there trying to make the most of it,” Bubba Garrett said. “She doesn’t take much for granted anymore.”

B. T. Wilson has been coming out to the Canyon for decades as part of the Foundation Camp program. Foundation Camp allows groups of all kinds—churches, schools, and other nonprofits—to use facilities in the Canyon free-of-charge. The bulk of the groups wouldn’t be able to afford camp otherwise. They stay in the cabins and bring in their own food to eat in the dining halls. While every group is expected to have a character-strengthening curriculum, they are given a good deal of freedom to program the three-day retreats to meet their group’s unique needs. Some groups opt for lots of free time, while others structure the day around team building and organized outdoor experiences.

B. T. Wilson has used the retreat in a special way: bringing together sixth graders who don’t yet really know each other and preparing them to spend the next seven years together.

Students from Kerrville ISD’s four elementary schools converge in sixth grade, creating what can be an overwhelming social change for many, all while they figure out hormones, lockers, and free seating in the cafeteria.

In 2002, the district created a special campus for these transitions: B. T. Wilson Sixth Grade School. The leadership at B. T. Wilson almost immediately began taking students to the Canyon to further equip them for what lay ahead.

It’s the perfect setting for students entering a new phase of personal, social, and emotional development, said Sam Rylander, regulatory compliance administrator for the H. E. Butt Foundation. In previous positions, Sam has worked with both Foundation Camp and Outdoor School.

Outdoor education puts kids in new settings where no one really has an advantage over anyone else. Experiences like archery, canoeing, and water science—things they don’t do in elementary school—are new to almost all the kids.

“It’s the very nature of bringing kids into an environment that is not their normal environment and doing things outside their comfort zone that causes them to learn new things,” Sam said. As they learn, they learn something new about themselves.

Matt Attridge is a senior this year, and he said it’s taken him this long to fully realize all he learned at Outdoor Ed. When he arrived in the Canyon, he was skeptical. As an introverted sixth grader with some scouting experience, he worried that Outdoor Ed would be a “glamping” experience, programmed to favor extraverts—the kind of camp where outgoing, confident kids have a great time hamming it up in skits and games and everyone else just sort of cheers them on.

That’s not what Attridge found. By the first night it was clear: they were here to grow.

“[The school’s leadership] was trying to pull something out of you. To show you something about yourself,” he said.

During the three days of Outdoor Ed, Attridge said, the adults on the trip helped him reflect on specific moments, things he had said or done during activities, how he’d handled social or teambuilding situations. They helped him see signs of his own leadership in those moments, and how to cultivate it. At the end of the three days, they gathered to debrief and listed the various lessons learned, highlighting the ways students had stepped into leadership in subtle or unexpected ways.

“It opened our eyes to the fact that we are all capable of being leaders,” Attridge said, “But we don’t show it if we’re too closed off within ourselves, too worried about what other people think.”

Thinking of himself as a leader has encouraged Attridge to pursue other opportunities. With each experience—for instance, he recently attended a Military Order of the World Wars conference—more and more of what he learned in the Canyon starts to make sense. In one exercise, as he and his team tried to create a three-month living budget for an entire town, they realized no one knew much about economics. No one had enough expertise to guide the project.

Attridge knew, however, that leadership isn’t always about expertise. The leader isn’t the one with all the knowledge or the prowess within themselves. The leader is the one who can get the rest of the group moving forward, gathering and sharing knowledge and skill as a team.

“It had me coming back to those things they were saying at the last gathering” at

B. T. Wilson’s Outdoor Ed, Attridge said.

In the conference exercise, he found himself in the role of lead question-asker.

Parents and teachers hope that at some point a student’s childlike understanding of leadership and confidence changes from something that is black and white—you either have it or you don’t, and it must look and sound a certain way—to something that is brilliantly colorful. Confidence can blossom quickly or take time. Leadership can manifest in unique, authentic ways.

“You never know when a child is going to connect the dots,” Sam said. “Outdoor education diversifies the spaces from which children can begin to pick up these lessons.”

These subtle nuances to leadership and confidence, like Evie Garrett’s generosity and Matt Attridge’s willingness to ask questions, are things adults might try to teach their children or students, but really, it’s wisdom. Wisdom gained from watching, listening, and doing.

For many Kerrville ISD students, the path to wisdom passes through B. T. Wilson and three days in the Canyon.

Cypress trees line the Frio riverbanks, providing shade, respite, and inspiration now and for hundreds of years to come.