Sometimes, the winter sun can take your breath away. That was especially true in January as I stood with several Native Americans who were visiting the H. E. Butt Foundation Camp for the first time.

Our first stop was the top of Antenna, the tall tower overlooking Echo Valley that powers our Canyon radios and serves as a mountaintop amphitheater for groups to gather and worship.

“I know why this land was sacred to so many people,” said Rudy De La Cruz. He is the director of the Texas Heritage Project for the American Indians in Texas at the Spanish Colonial Missions (AIT-SCM) and a descendent of the Coahuiltecans (kow·aa·weel·tuh·KAN), though he doesn’t know which tribe. Rudy’s grandfather was a foundling, dropped off in 1915 at an orphanage run by Father De La Cruz, “so that became our last name.” Rudy is tall—well over six feet—with a long black ponytail. He wears a plaid shirt, a small pouch of medicine around his neck (sage, he tells me), beads made from Mountain Laurel beans and wood, a star of David, and a cross. His grandfather, Rev. Manuel De La Cruz, started Assemblies of God churches all over Texas—from Lubbock to San Antonio.

That day, looking out over the Frio River as it bends around Echo Valley, Rudy started the tour by reading a land acknowledgment he had written for the Circle Bluff Area. Land acknowledgments can take different forms, and for Rudy this was a poetic and historically researched acknowledgment of gratitude for the many different people who have visited the Canyon over the centuries. His words felt very much like a prayer.

“Eternal Creator, we gather here today to show our respect to the Ancestors and with cries of victory acclaim the resiliency, tenacity, and ability of Native American peoples of today to survive, heal, and thrive.” He prayed that our hearts would be protected. He named several dozen nations, tribes, and bands who have lived in this part of Texas for centuries—the Pacoa, the Tepehuan, the Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation, and so many others. He prayed that our words would be words of healing for all generations.

After his prayer and acknowledgment, no one spoke for a while. The silence felt holy.

“Eternal Creator, we gather here today to show our respect to the Ancestors and with cries of victory acclaim the resiliency, tenacity, and ability of Native American peoples of today to survive, heal, and thrive.”

Creator Sets Free [Jesus] answered him, “You must love the Great Spirit from deep within, with the strength of your arms, the thoughts of your mind, and the courage of your heart.’ This is the first and greatest instruction.

“The second is like the first,” he added. “You must love your fellow human beings in the same way you love yourselves.’

Matthew 22:37-39, First Nations Version

Then Jesús Reyes Jr., an anthropologist and language expert, offered a hymn in his ancestral language, asking forgiveness that people have not always been good stewards of the land. He is a Tap Pilam tribal elder. “It’s pronounced Taapiił amm,” he explained, and I struggled to pronounce the words back to him. Jesús’ tribe is one of the 250+ indigenous groups collectively known as the Coahuiltecans because they shared trade routes across Texas and the Mexican province of Coahuila. “Coahuiltecan is a convenient way of grouping them,” Jesús said.

For several years, the Foundation has been partnering with American Indians of Texas through our capacity building program and our storytelling initiative. We featured their fatherhood building program in our Summer 2021 issue of Echoes. At our suggestion, Rudy invited several tribal members and elders to explore the property in person and help us identify middens. Together, we hoped to better understand which tribes specifically would have visited the Canyon before us. Long before us.

Recent findings at the Gault Archaeological Site north of Austin suggest people have lived in Texas for more than 16,000 years, much longer than previously thought. In the past, experts have estimated the ancient middens on our property—mounds of fired limestone that were used as ovens for cooking and toolmaking—are thousands of years old.

These middens were our goal for the day, and we were soon hiking to the next location on our Canyon tour, a potential midden near Silver Creek. Kevin Wessels, Director of Stewardship for the H. E. Butt Foundation, led the way.

Altogether, four Native American guests from AIT-SCM joined us—a young woman, a young man, and two elders. Four of them represented Coahuiltecan tribes who had likely migrated through the Frio Canyon each year for centuries. Lindsey Bruce, a graphic designer for the H. E. Butt Foundation, also came. She is Kiowa: a tribe which was known to trade with the Coahuiltecans.

“It’s no coincidence that a Kiowa is here with us,” Jesús said. “Just like we would have done years ago when the people would meet to trade.”

What is appropriate interaction?

When we reached the midden, Jesús surveyed the site visually, showing us discolored limestone rocks that were broken at right angles. He interpreted the rocks to have broken under heat stress, like they might have experienced in a midden oven.

Given that neighboring ranches have verified middens on their properties, it is safe to assume this is a midden as well, Jesús told us. To know more, we would have to study it more closely, perhaps even dig into it. Should we?

“What is the appropriate way for us to interact with these middens?” Kevin asked.

That question opened up an energetic conversation because our guests had mixed feelings. As Native Americans, they advised us to leave the middens alone. But as archaeologists and anthropologists and historians actively working to rediscover their heritage, they hoped we would study and document. “Working with both [the Tap Pilam] Nation and archaeologists will allow for a more holistic approach,” Jesús agreed.

Our Canyon trail maps already caution guests, “If you find a fossil or arrowhead, please do not remove it. The location of artifacts and fossils provides crucial historical context.” (In fact, we debated internally whether we should even write publicly about the hundreds of middens on our property.)

The second midden we visited, after a delightful box lunch at Blue Hole, was smack dab in the middle of a campsite. A game court is right next to it. Guest beds and outdoor seating are very close.

As soon as we approached the midden, both Jesús’ and Rudy’s eyes lit up. This was definitely a midden they assured us. There was no doubt this time, no need for further surface investigation. Jesús picked up several rocks, marveling at the sheer size of the site.

Rudy said ancient sites like these fill him with a sense of belonging. Here, just outside one of the main buildings on the H. E. Butt Foundation property, an ancient midden utilized by Native Americans demonstrates that he belongs. It asserts his identity and heritage for him

“Healing would bring them here.”

It’s a funny thing, heritage. The Canyon is a place where people still gather to play games, to tell stories, to retreat. Many guests are on a spiritual retreat of some kind. Their drive in the river is special, almost baptismal, set apart, and somehow holy. Our guests today experience the Canyon as a place of healing—likely the same way it may have felt to the Coahuiltecan ancestors we are remembering today.

“Healing would bring them here,” Jesús said, “for the water, the animals, the plants … We are healing now. With the sunrays. With the conversation. And the prayers. I would like to come back and pray some more.”

Prayer is the best way to show respect, Rudy agreed. “I like to say words and offer respect and gratitude and wonder. There’s a simplicity out here that makes you not want to go back … It’s a lifelong journey to find what you were before, and I wonder if [the ancestors] know that we are being allowed to be ourselves again.”

This land contains the legacy and culture of so many people. Many of them—including many ancestors of the Tap Pilam Coahulitecan Nation—still live near enough to visit.

Mary Holdsworth Butt and Howard Butt Sr. expressed their specific interest in preserving the history associated with the H. E. Butt Foundation Camp property. In an excerpt from Mary Holdsworth Butt’s diaries, she writes, “… both of us want to preserve historical facts as well as historic value.”

This history of the people who were here before us—the mystery of the past—is part of what we steward as we care for this land and share it with others. Remembering is a way of honoring our neighbors from the past. Because what are ancestors except neighbors who came before us? The ones who played games in these fields before we did, who fished these waters before we did, who loved this Canyon before we did.

It is good to be thankful for the people who loved this land before we did. They are part of the story of this place today as much as we will be part of the stories others may tell in the future.

“I call it the song of the ages,” Rudy said. “To meditate on what has been, what came before.” Respecting the past does not require shame, only humility.

“Is there anything you would want to say to other guests?” I ask.

“Even after all of the story since we were here, we still love you,” Rudy said. All of the story. Such a gentle reminder of such difficult struggles.

“We accept you,” Rudy said, “and hope you can accept us. This place and our people’s evidence [here] gives us hope.”

“We accept you, and hope you can accept us. This place and our people’s evidence [here] gives us hope.”

If you have seen older trail maps for H. E. Butt Foundation Camps, you may have read a misleading version of our history. We accurately described the shallow sea of antiquity that would have included giant Cretaceous turtles, but we listed Lipan Apache and Comanche as the primary Native American groups who would have migrated through the Canyon rather than Coahuiltecan.

On these misleading maps, we included a beautiful and haunting photograph of Apache riding away from the camera. But there are a few problems with that picture. First, the Apache in the picture are not Lipan Apache. Second, they are riding in Arizona, nowhere near the Texas Hill Country. And finally, the picture communicates metaphorically that our country’s indigenous people have disappeared. But that’s not true. Rudy De La Cruz reminds people often, “We’re still here.”

Revised maps will include artist renderings of the Coahuiltecans, plus photos of their descendants who still live around the San Antonio missions their ancestors built.

“I call it the song of the ages—to meditate on what has been, what came before.”

Rudy De La Cruz

The land we call Texas lies at the bottom of a large Cretaceous sea connecting the Gulf of Mexico and the Arctic Ocean.

The first people arrive in Texas 16,000 years ago, according to new materials discovered in 2018 at the Gault Archeological site near Florence, Texas.

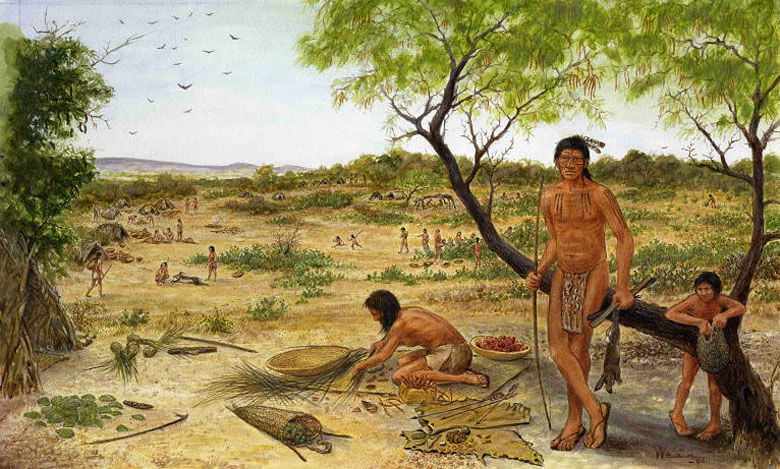

About 10,000 Coahuiltecans likely populate the area, living in family bands of 100-300 people, harvesting mesquite beans, prickly pear, local fish, and whitetail deer.

Image courtesy of the Museum of South Texas History.

The first of three Papal bulls begins to establish a theology of colonization, later known as the “Doctrine of Discovery.”

Christopher Columbus sails three ships sponsored by the Crown of Castile in Spain to Guaahani, an island in the Bahamas.

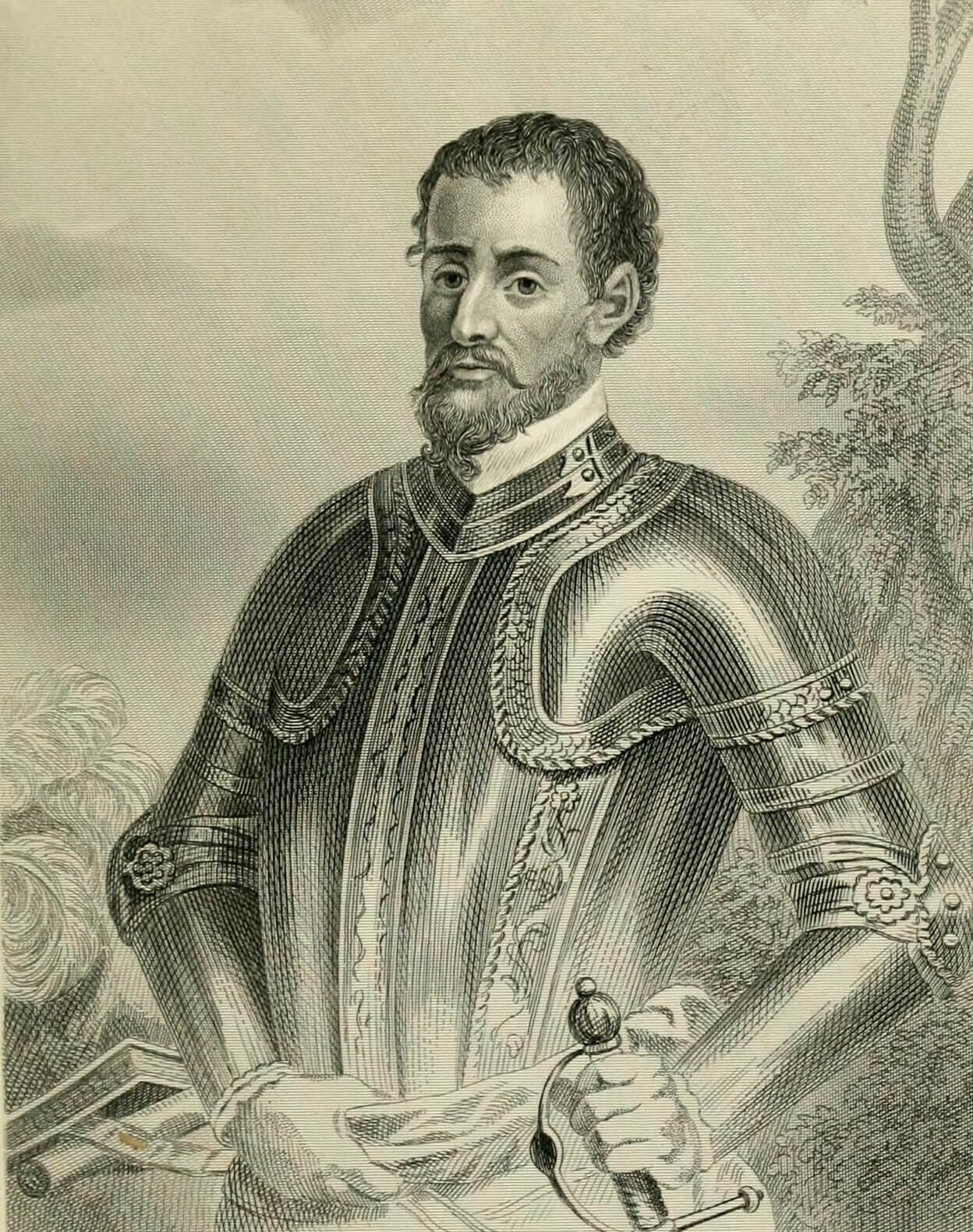

Cabeza de Vaca publishes about his travels from the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of California and sympathizes with the indigenous people he meets along the way.

Lipan Apache enter Texas from the Great Plains and settle in the Hill Country. Their name “Lipan” means “Light Gray People.”

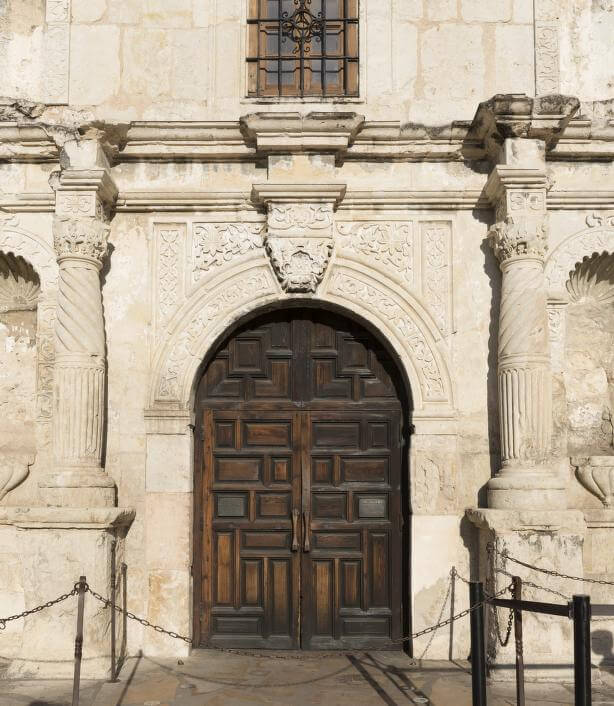

Mission San Antonio de Valero (the Alamo) is established by Franciscans under Fray Antonio de Olivares. It serves approximately 50 different local tribes who lived throughout the Hill Country.

A small band of Comanche visit San Antonio, probably on a scouting mission. This is the first documented evidence of Comanche in Texas.

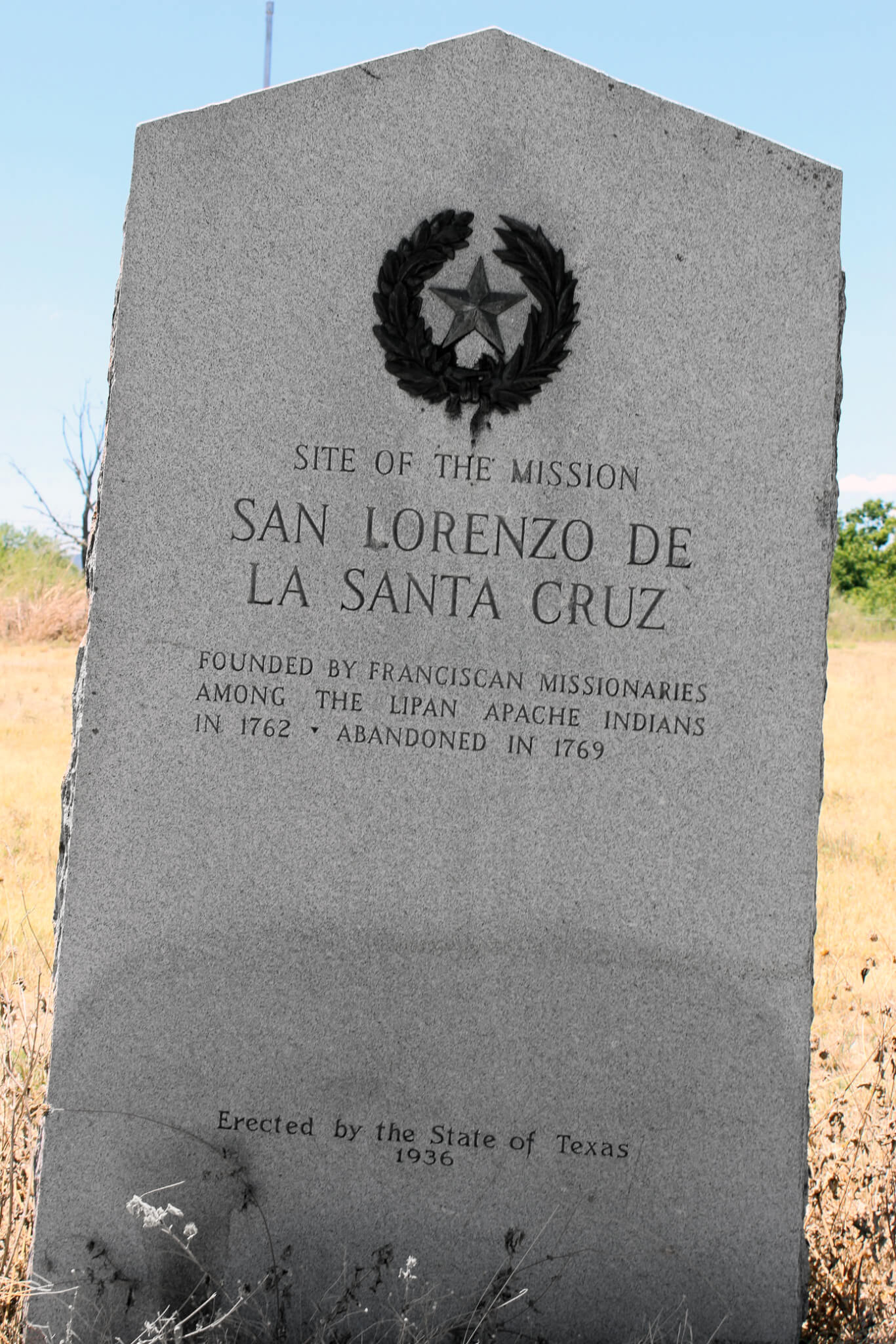

Franciscans establish Mission San Lorenzo De La Santa Cruz in Camp Wood near the Frio Canyon.

The United States declares independence from Britain.

Texas declares independence from Mexico, establishing the Republic of Texas.

John and Nancy Leakey settle along the banks of the Frio River near present-day Leakey.

The McLaurin Incident, one of the last skirmishes with Native Americans in the U.S., occurs several miles from camp. Two settlers and an entire band of Lipan Apache are killed.

Howard Butt Sr. and Mary Holdsworth Butt purchase the property from the Wolfe family, establishing the H. E. Butt Foundation Camp “to care for at least 100 children at once.”

The American Indians of Texas at the Spanish Colonial Missions (AIT-SCM) is established as a nonprofit organization by the Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation.

Members of the Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation and H. E. Butt Foundation employees visit the Frio Canyon together.

This new indigenous translation from InterVarsity Press offers a fresh rendering of the Gospel utilizing the beauty, clarity, and simplicity of Native oral storytelling. It received a Publishers Weekly starred review and won Reference Book of the Year from the Academy of Parish Clergy.

Visit the organization that has worked with the H. E. Butt Foundation for several years, browse their timeline of events, click on the video thumbnail for a virtual tour, or sign up for an in-person tour of the San Antonio Missions by Coahuiltecan descendants of those who built the Missions.

Texas Beyond History (TBH) is a public education service of the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory (TARL) at the University of Texas at Austin. The content on the site is written, published, and reviewed by leading archeologists and anthropologists.

This 1964 book from the University of Texas Press remains one of the best general works on the native peoples of Texas, including 30 pages dedicated to the Coahuiltecans.

This historic 1859 publication was the “principal manual for westward-bound pioneers.” Although it contains problematic language by today’s standards, it remains an important resource for understanding the prejudices many immigrants brought with them as they moved west.

From the University of Oklahoma Press, this work by scholar James L. Haley explores the culture of the Apache Nation as a way to understand the troubled relationships between Apache and the U. S. military in the 1800s.

T. R. Fehrenbach’s history of the Comanches is widely considered one of the best of its kind: “a classic account of the most powerful of the American Indian tribes.”

Mark Charles, a descendant of Navajo and Dutch Americans, and Soong-Chan Rah, a professor at North Park Theological Seminary, explain the controversial Doctrine of Discovery through the lenses of “history, theology, and cultural commentary.”