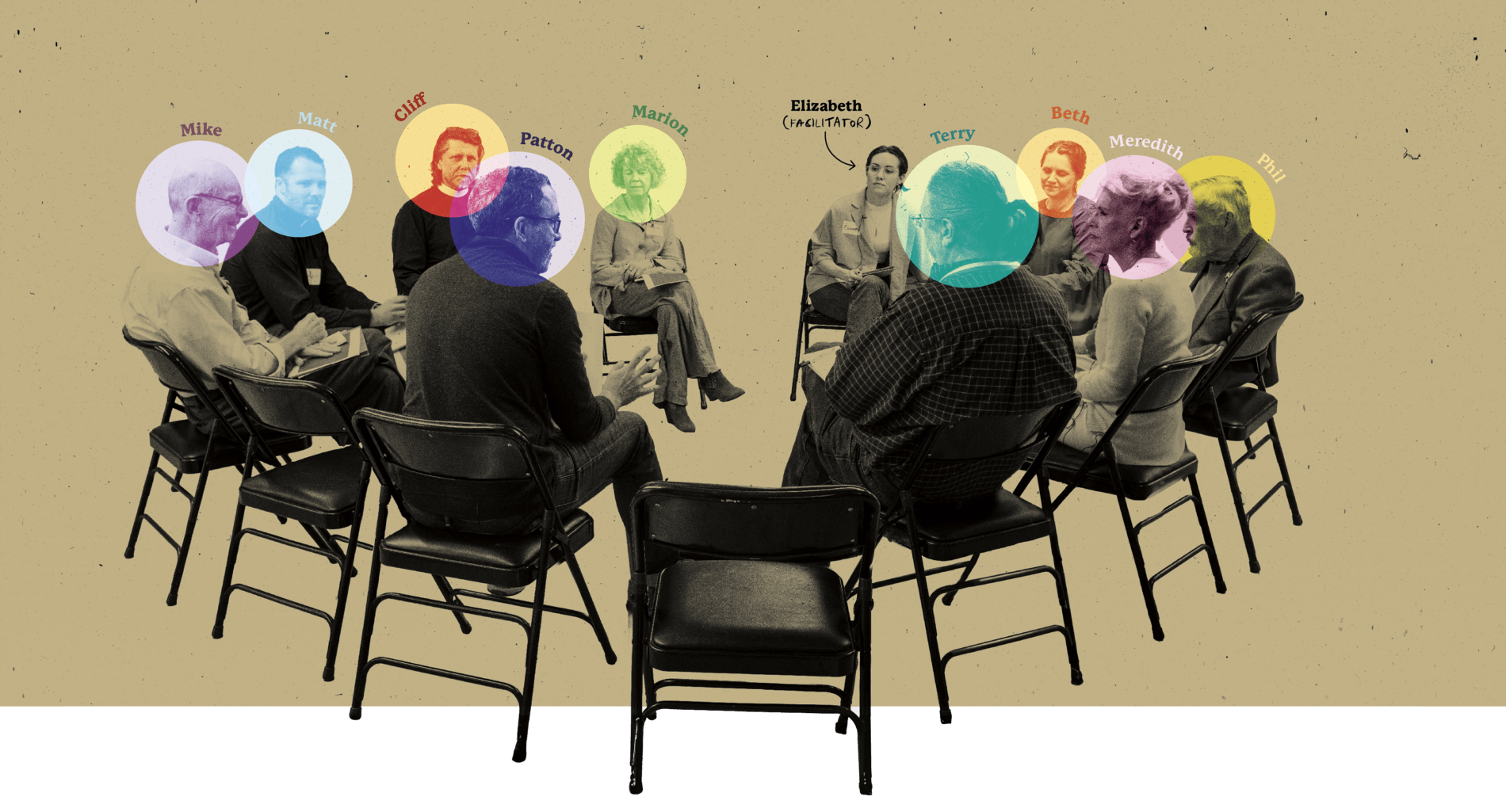

Participants gather in Austin to discuss the questions in our 2023 community survey.

Words by Beth Avila | Photos by Wendi Poole

An overcast mid-March Sunday turned into pouring rain just as participants began to arrive at the Foundation’s roundtable discussion in downtown Austin. Despite the weather, nine of us made our way into the space Christ Church had provided. Seated in a small circle, our group was ready to talk— and to listen.

Everyone in the circle had responded to the Foundation’s 2023 community survey, which was designed to help us find out how participants feel about the most pressing issues in their communities today. The purpose of the gathering: to get a few people together to discuss in person the same questions that the survey asked thousands of people anonymously.

But the discussion didn’t start with community struggles.

It started with neighborhood tours.

“If you were giving a tour of your neighborhood to somebody who had never been there before, what is one place you’d want to include and one place you’d like to avoid?” asked Elizabeth Coffee, the director of storytelling for the Foundation, who was facilitating that day’s discussion.

“I live in a nondescript northern suburb of San Antonio. We’ve been there almost nine years and I have a hard time inviting people over,” Patton lamented. (In this story, we’re only going to identify participants by their first names.) “It has a big gate, which is conspicuous and stupid.”

Similarly, Meredith shared, “We have very big homes with large lots … When I go to a neighborhood gathering, I’m so blown away by just how over the top it feels.”

“The place I would avoid is this street where the most powerful people in the neighborhood association live,” said Terry. “It’s where the retired constable parks his vehicle to ‘keep out the wrong people.’ It’s where all the people live who seem to hate everyone.”

Others mentioned ugly parks, strip clubs we wished would go away, and cranky neighbors. But when talking about where we would take someone on our hypothetical tours, a major theme emerged—connection.

“I live in Pemberton Heights. We had a Texas French Bread that burned, and now it’s this bakery share where you can get a bakery bag and share it,” said Marion. “One time I missed the pickup, so the owner brought me my bread, which is so nice. And I often see my neighbors’ names on the bags all sitting out for pickup. It makes me happy.”

Matt also described connecting with his neighbors via basketball and Google Translate.

“I’ve lived in southeast Austin for six years now. We have three kids, and our next-door neighbors have four kids. They don’t speak English, and we don’t speak Spanish,” he laughed. “But we have one of those pop-up basketball hoops, and a couple times a week we have eight to ten kids playing basketball right out front, while I play referee. It’s a fun place to be.”

I commented on the great Mexican food at El Mirasol that I enjoy with my husband near our neighborhood in Boerne. Cliff mentioned taking someone to Taqueria Chapala, where his family has been eating together for 18 years.

All the places and moments of connection that our group mentioned went to show how essential relationships are to a thriving community.

“I think loneliness is a problem that seems to have increased in the past decade,” said Cliff. “From COVID and the isolations of that, to working remotely, to social media and the ways that can replace getting together in person. “In Austin, it’s really compounded by traffic. For the people who don’t live right around here, it used to be an easy thing to come up midweek and do this thing or that with the church, but now it’s an ordeal.”

But it is more than just traffic driving a wedge in community relationships.

“Austin is such a diverse and cool place. We need to be able to embrace our differences without erasing them and without hating each other,” said Terry.

“Everybody is looking for someone that jives with them in every possible way, and if they find a way that you don’t jive with them, then they believe they are wrong for doing anything with you.”

Terry continued, “We have reached the conclusion that we are somehow less than if we work with people who we disagree with on some other topic. Differences aren’t new to us. Austin has always been rich and poor, liberal and conservative … but it’s only become hatred within the last decade, and we need to reverse that.”

The word “community” can mean different things—our neighborhood, our city, or the people we care about. For Marion and Meredith, community includes their workplaces.

“Most of my friends are grandparents and focused on helping support our children and grandchildren. And most of them can meet that need for support. But the community I’m 50% or more involved with is my work community—a group of child-life specialists focused on providing support for parents and families when the parent has a serious illness or injury,” Meredith said.

“Most of my friends are grandparents and focused on helping support our children and grandchildren. And most of them can meet that need for support. But the community I’m 50% or more involved with is my work community—a group of child-life specialists focused on providing support for parents and families when the parent has a serious illness or injury,” Meredith said.

“The economic needs when injury or illness strike can be devastating, and then you layer upon that the trauma of the illness or injury itself. My work community needs mental health and economic support.”

“I, too, see a lot of mental health things,” Marion chimed in. “Teens have been hurting for a while. It’s such a big part of my work now, and I’m not supposed to be a mental health provider. I take care of hospitalized kids, and a third of my patients probably have some mental health concern that is manifesting physically.”

Naming a solution to complex issues like mental health felt overwhelming for the group.

“I wish there was more mental health support in schools,” said Marion. “But then teachers would need to get paid more to be better resources. And the parents often need more support too. It’s all tied together—economic support, child support, mental health support.”

“I wish there was more mental health support in schools,” said Marion. “But then teachers would need to get paid more to be better resources. And the parents often need more support too. It’s all tied together—economic support, child support, mental health support.”

One thing was clear—our group, as well as other participants in the community survey, desired to show God’s love to others.

“Everyone has value, and we are incomplete without them. We are less when we leave them on the outside,” said Terry.

“We have to get to know individuals personally and what their specific needs are to better love them,” said Meredith.

“We say the church should love, but to me love is always abstract until it’s grounded in neighbor,” said Matt. “Love is defined by knowing who the literal people in my community are. We are to love them as Jesus loves them—to meet them in friendship.”

“We say the church should love, but to me love is always abstract until it’s grounded in neighbor,” said Matt. “Love is defined by knowing who the literal people in my community are. We are to love them as Jesus loves them—to meet them in friendship.”

When Elizabeth asked if there were any final comments, Phil, one of the eldest (and possibly wisest) of our group, responded by quoting Matthew 22:37-40:

“Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: Love your neighbor as yourself. All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.”

“And who is my neighbor?” Phil asked. “As far as I can tell, anyone I come in contact with.”

What resonates with you—a particular scripture or poem or quote—when you need strength or inspiration?

68% of survey respondents said supporting people living on the margins was a top priority for their faith communities.