Let’s start with 17-year-old Isabella Lookingbill, a senior at East Central High School. The first time she heard people talk about issues like depression, anxiety, and loneliness was at church, during personal testimony time.

Fellow congregants stood up in front of the church to tell them about how God had helped them find hope in hopeless times or calm their dark and nagging fears. Lookingbill realized how common it was for people to live with some degree of mental suffering.

“Hearing those testimonies, I hear that people struggle every day,” Lookingbill said. “It’s a very silent fight.”

At school, she said, she knows the kids around her are struggling, even if she can’t always tell you who or with what. Her classmates pile on activities to try to round out their college applications, and the stress is daunting. Some won’t text their friends back for days, but post smiling photos on Instagram.

Everyone is making it look good, Lookingbill said. “You put that smile on and we might be friends, but I don’t know what’s going on at home.”

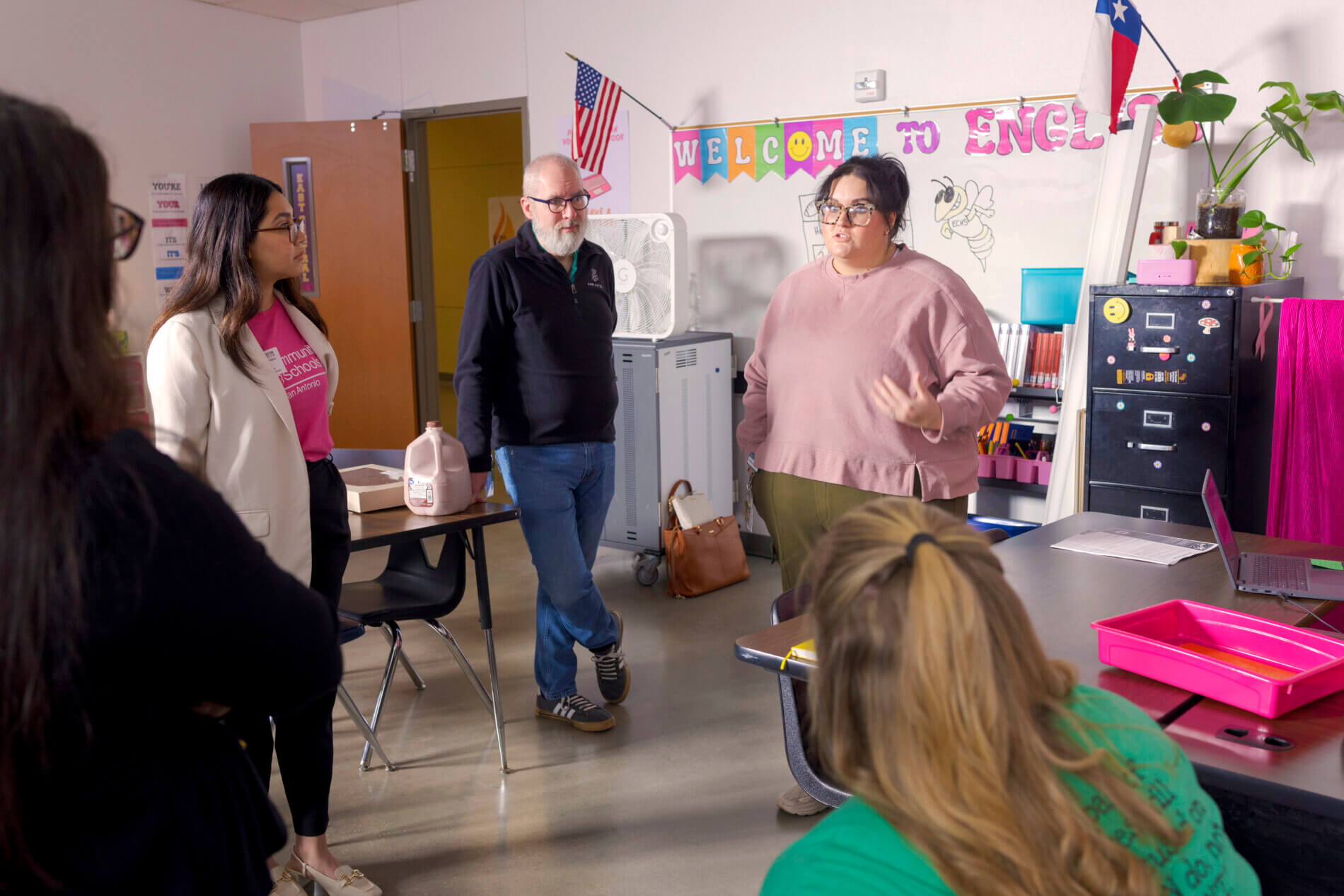

Today, Lookingbill is the social media manager for East Central High School’s Mental Health Club, which meets before school with both teachers and students to discuss different ways to bring mental health training and resources onto campus.

One of the club’s sponsors, English teacher William Toney, is a licensed clinical social worker who spent 25 years in practice. Six years ago, he decided to become an English teacher, in part as a continuation of his mental health work. He was going where he knew the need was, and upon arrival soon found himself doing “some old school social work.”

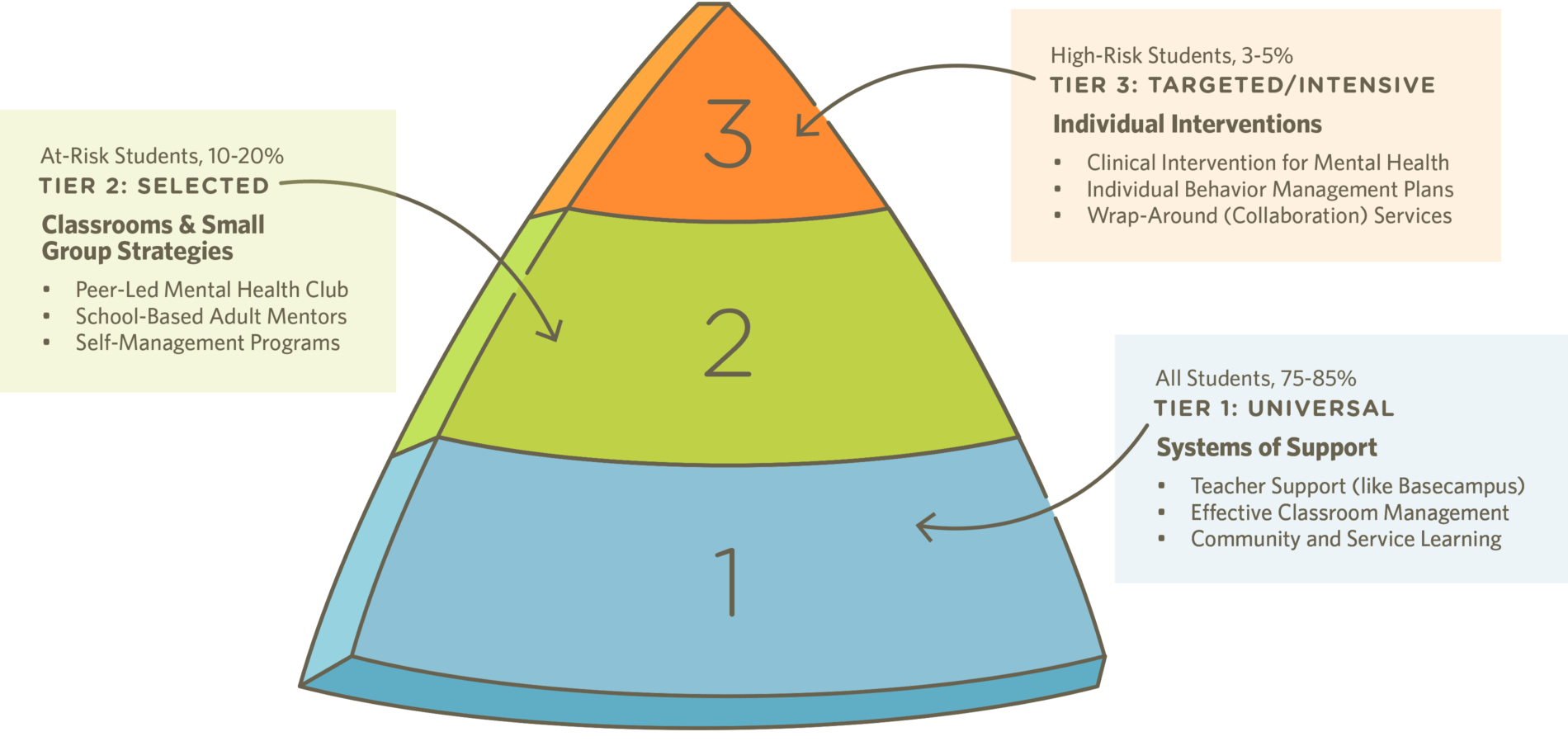

A student club may seem like a small thing, but it’s part of a multi-tiered system of support—think of it as mental wellness infrastructure—that has been several years in the making.

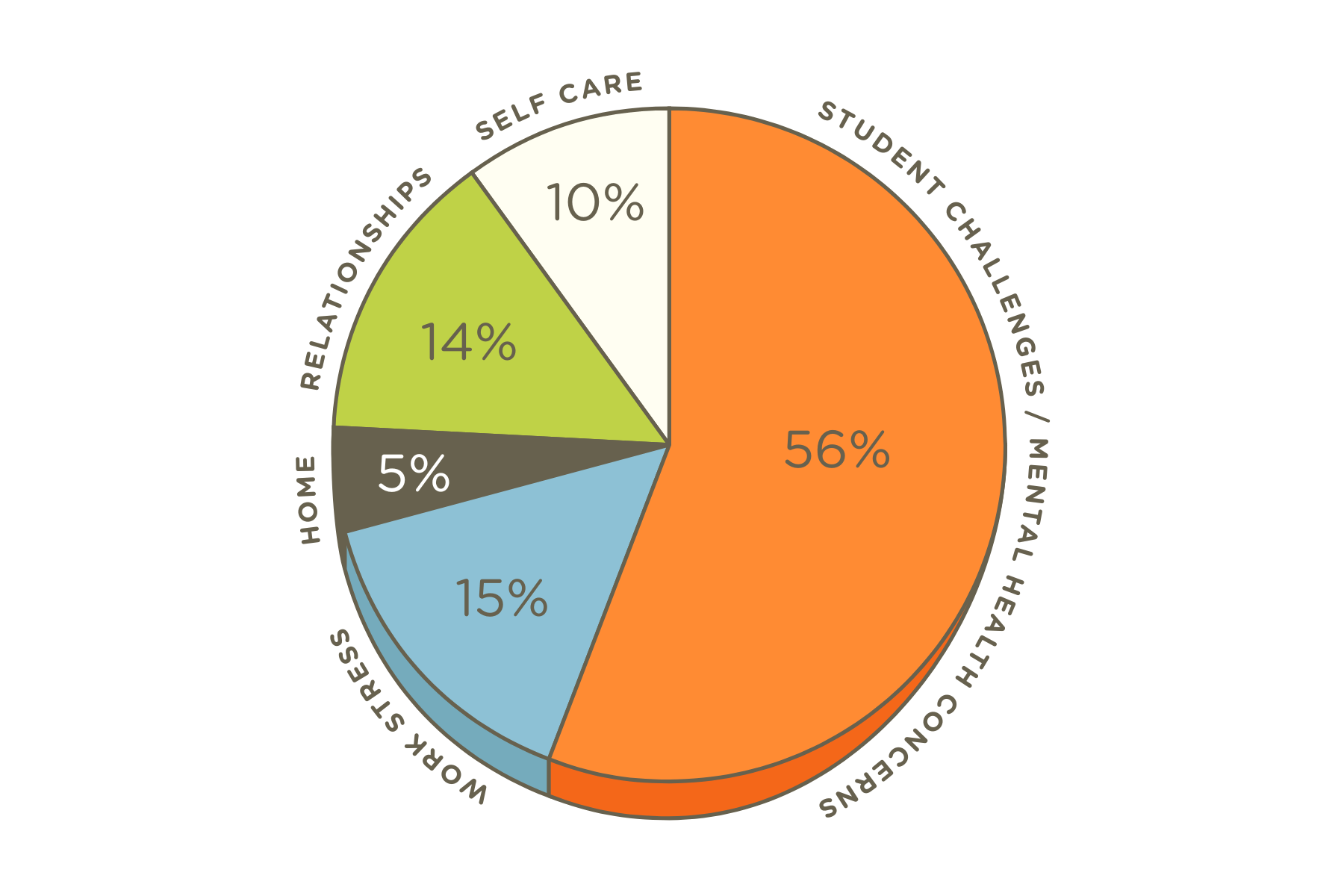

In 2016, the H. E. Butt Foundation convened community partners—Child Clarity Guidance, Communities in Schools, and local districts in San Antonio—to determine how to improve mental health for teens. The group decided to focus on one support for teachers—coaching them on how best to engage with students around mental wellness and how to care for their own mental wellbeing.

According to research, many teachers are under so much stress that they are more at risk of mental health disorders than those in other occupations. More importantly, when teachers have good mental health, their students also tend to have good mental health.

Based on these findings, the same local partners worked with the H. E. Butt Foundation in 2018 to develop a pilot program designed to serve teachers based on a theory of change arising from the research: When teachers have better mental health, they can better support the mental health of their students.

In the pilot, which was called Basecampus, Communities in Schools hired a licensed social worker to serve as a Social-Emotional Wellness Coach on campus, providing full-time support for teachers, administrators, and support staff.

By 2021, Communities in Schools and the H. E. Butt Foundation focused the Basecampus pilot at East Central High School, allowing teachers to meet with a licensed professional counselor on campus to talk about their own stress, anxiety, and frustration. That’s important, Toney said, because the healthier a teacher is, the more attentive and helpful they will be for their students.

“It can be really tempting to take (student behaviors) personally,” he said. But when the teacher is healthy, they can stay focused on the kids and use the troubling behavior as a way to start a conversation about the struggles that may be motivating it.

Mental wellness is just as important as physical health and academic progress.

Today’s high school students seem perfectly literate in therapy talk or clinical language, but Lookingbill said that actually seeking help or putting healthy habits into action is rare. Knowing your mental health is in the gutter doesn’t necessarily mean you can get it out.

Data supports her observation that students might need help, but they largely aren’t getting it. The Centers for Disease Control found that between 2011 and 2021, the percentage of high school students who experienced persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness has increased from 28% to 42%.

This means only 58% of students are sufficiently served at the Tier 1 level by their teachers, while staff providing more targeted interventions are overwhelmed. A 2024 Mental Health America survey found that over half of the students who had major depressive episodes that year had not received professional help.

If students don’t find help in their schools, most teens won’t find help at all. How can they get themselves to therapy when they are in class during the majority of working hours, dependent on parents for a ride, or struggling to juggle extracurriculars? Most cannot. This is especially true in places like East Central ISD, where Lookingbill goes to school.

Throughout the state, Texans have insufficient access to mental health professionals, services, or facilities, leading to unmet needs for care. According to the Texas Department of State Health Services, 246 out of 254 counties have a shortage of mental health professionals. Not counting federal dollars through Medicaid, Texas’ budget in 2015 for behavioral health ranked 49th in the United States.

In Bexar County, mental health facilities are currently operating at 120% capacity, according to data from the Center for Health Care Services. In Southeast Bexar County, where East Central is located, the need is critical, with extremely limited mental health facilities and providers, according to an analysis by University Health System.

Putting mental health resources on school campuses removes a major barrier, according to Jessica Weaver, executive director of Communities in Schools – San Antonio, whose organization largely ran the Basecampus pilot. Providing on-school resources, they found, eliminates the time, logistical challenges, and cost burden that stands between teens and the help they need—and know they need.

“Anytime there have been youth asked what their main priority is, mental health comes up,” Weaver said. Their comfort with the term “mental health” shows how much they understand it. According to Weaver, mental wellness is just as important as physical health and academic progress. While each student might have a different journey through their unique struggle—be it anxiety, depression, loneliness, or something else—most are aware that the journey needs support.

Communities in Schools continues to provide that support in several ways. Data from the Basecampus pilot, alongside other programs, proved catalytic for the organizations involved, helping them secure a $7 million federal grant supporting mental wellness at East Central ISD. As a result, case workers and clinicians currently have offices on school campuses, and they support teachers like Toney and teach students like Lookingbill to recognize signs of struggle.

Sometimes a budding mental health challenge can be addressed by a listening ear and a reminder that the student is not alone. And sometimes students need to hear, “It’s time to call in help.”

While school districts cannot afford to hire enough campus-based counselors to make intensive in-school counseling available for every student, the Basecampus pilot provided evidence that teachers can provide meaningful intervention at the tier one level. When teachers are trained to recognize mental health challenges, they can either provide appropriate support or know when it’s time to refer the student to a counselor—similar to how you would train a staff member in physical first aid.

Teachers don’t have to be clinicians like Toney. They just need to be caring adults, Weaver said, willing to help kids sort through their confusion, pain, and questions. “If a high school kid can find an adult to talk to, they will,” she said.

A safe listener opens the door to help. The key, Toney said, is to recognize that the kids’ behavior, whether sleeping in class or outbursts of frustration, is not rebellion. These are not unappreciative kids. Many of these students are taking on huge responsibilities in their families and managing more scrutiny and pressure than previous generations might understand. “Don’t assume you know what they are going through,” he said.

When more people on a campus can listen with empathy, openness, and calm, fewer students will carry their mental health challenges to the point of crisis. “They need to believe they’re going to be heard,” Weaver said.