At Olmos Elementary School in North East Independent School District, family specialist Lilliana Esparza’s days never go as planned. They begin with tutoring, a service the campus provides before and after school every day. From there, she responds to whatever needs arise. Needs always arise.

Esparza is part of a team of specialists who provide wraparound services to the students and families of Olmos. In education, wraparound services usually include mental health and social services to help kids enter the classroom ready to learn. At Olmos, Esparza said, this includes breakfast, lunch, snacks, clothing, bedding and hygiene products. She stocks a food pantry and clothes closet with community donations, and the school provides meals.

Making home visits, Esparza often sees the source of a child’s anxiety and distraction. When she visits public housing apartments, she sees deferred maintenance issues and infestations that interfere with the health and safety of the children. In some single-parent homes, she sees a lack of supervision as the parent works long hours to provide for the family.

Many times, these challenges manifest in the classroom. Watchful teachers call Esparza to observe behaviors that send up red flags. Ordinarily quiet kids lash out suddenly. Ordinarily confident children are suddenly timid. All of these can indicate that something outside the classroom is amiss.

“A lot of things that we noticed are things we take for granted,” Esparza said. “Do you know what it’s like to have your lights turned off?”

Lilliana Esparza prepares to distribute holiday food donations at Olmos Elementary School. Bekah McNeel / Folo Media

Poverty goes to school

Poverty, no matter how you define it, is a challenge. Schools often amplify that challenge.

Traditional schools are designed to deliver educational services at a level that assumes certain resources are available to the student at home and through their community, Northside ISD Superintendent Brian Woods said. When a student comes to school weighed down by issues of homelessness, hunger, or other forms of instability, they can’t always retain knowledge in a system designed for well-rested, nourished and emotionally stable kids.

When a child is distracted, fidgety, fearful — or acts out — Esparza asks, “What need is being unmet?”

Last year, while embarking on a listening touring of the 55 schools in his district, State Rep. Diego Bernal heard educators in every school acknowledge that the economically disadvantaged kids faced greater barriers to academic success.

“Kids who are poor bring with them challenges that are not academic, but affect academics,” said Bernal, who represents San Antonio’s District 123 in the Texas House of Representatives. The issues could be as small as cramped housing without a quiet place to do homework, or as large as homelessness and chronic illness.

The constant unmet basic needs constitute a kind of chronic (or constant) trauma, said Shelley Potter, president of the San Antonio Alliance of Teachers and Support Personnel, the union that represents San Antonio ISD. In SAISD, more than 90 percent of students qualify for free and reduced lunch, a proxy for poverty as measured by the U.S. Department of Education. Chronic trauma, Potter said, is everywhere.

Students living in poverty also have higher rates of exposure to acute trauma, Potter said — single events classified as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Students with these experiences typically struggle with behavioral and mental health, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

“We didn’t have wealth, but we had a lot of richness,” Lilliana Esparza says explaining the empathy she has for the disadvantaged students she serves at Olmos Elementary School. Robin Jerstad / Special to Folo Media

The right person in the right place

Unidentified mental health needs become apparent at school, as children meet new stressors outside their homes, said Valerie Kozlovsky, a licensed counselor through Communities in Schools’ Project Access, which places licensed professional counselors in schools.

Communities in Schools is a national nonprofit that creates a support system around individual students at risk of dropping out of school. Site coordinators act as case managers, empowering students and families through community resources. Many times, that means bringing food pantries, clothing donations and mentoring onto campus.

Project Access brings mental health services onto campus as well. Counselors meet with students once per week for a recommended number of sessions; they also communicate with relevant adults in the child’s life to bolster support and handle aftercare for traumatic experiences. The position requires a professional license — a Licensed Professional Counselor, Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist, or Licensed Clinical Social Worker.

In addition to its family specialists, NEISD has contracted with Communities in Schools to place a Project Access counselor on each of the district’s campuses where Communities in Schools works, including Olmos. Like the family specialists, Communities in Schools is funded by federal money available to Title I schools, those with 40 percent or more children living in poverty.

In NEISD, director of guidance Natalie Hierholzer estimates that only about a third of the schools qualify for these funds. However, poverty is also connected to high mobility. If a family living in poverty moves out of their attendance zone, and the children move into a school with lower poverty rates, they can lose that wraparound service provided by family specialists and Communities in Schools.

Even in districts like South San Antonio ISD, where the entire district qualifies for Title I funding, Communities in Schools is often partially funded by grants. Each grant informs the Communities in Schools site coordinator’s focus, requires additional administration, and can be lost for various reasons. Earlier this year, Communities in Schools lost its grant for South San, because it didn’t score high enough on its application, in spite of strong outcomes and demonstrated need.

Today, Communities in Schools of San Antonio announced that, since August, it has raised the funds necessary to replace the $400,000 grant, which funded national college readiness program Upward Bound and college guidance services in South San ISD for 20 years.

“Although the initial news was shocking, we were confident the community would rally around our students who had put in hours of hard work into their dreams of going to college and suddenly found themselves without guidance,” said Melissa Kazen, executive vice president of Communities In Schools of San Antonio, in a press release ahead of Tuesday’s announcement.

Among the donors were Search Institute, Mays Family Foundation, Whataburger, Toyota, Wells Fargo Foundation, Guido Brothers Construction, as well as individual donors.

City Councilman Rey Saldaña, a graduate of South San High School, credits Communities in Schools for pointing him toward Stanford University.

Without specialists on campus, the wraparound needs fall to the counselor, who, Kozlovsky said, wears too many hats with too many students to effectively address the extensive scope of needs. Traditional school counselors can be tasked with academic initiatives and college guidance, with a case load of as many as 800 students. “There’s no way that person could really reach out to all of those kids,” Kozlovsky said. “If we could be more individualized, I think it would be a lot more successful and effective.”

Sometimes students are referred to mental health counselors in the community. This is also less than ideal, Kozlovsky said, because many students have a hard time arranging transportation, and low follow-through rates indicate many simply give up.

“Ideally you need the social worker, you need the counselor, you need the parent-family liaison, and you need a coordinated system,” Potter said. “I would say this is one of the most important issues we face as a district: figuring out how we systematically provide this level of support.”

Parents can also be a vital member of these teams, Esparza said, because they want the best for their kids. “We don’t judge the parents,” Esparza said. “We create a safe haven.”

In the family room at Olmos, Esparza brings in community partners that offer parenting, GED and citizenship classes. Parents can request bus passes and utility vouchers. Restaurants and elected leaders deliver special holiday meals, and Summit Christian Center provides Snack Paks 4 Kids food assistance to help feed kids on the weekend.

Those who want to volunteer, donate or receive services don’t have to check the calendar first. Esparza is always there, and she’s always on.

Without wraparound services, teachers are sometimes left to address the needs of disadvantaged students — which can be taxing for the teachers, experts say. Special to Robin Jerstad / Folo Media

Letting teachers teach

On campuses without effective wraparound services, teachers often become the ones trying to address students’ needs, leaving them distracted from their jobs, Potter said. It’s an issue she sees reaching epidemic proportions in SAISD. It comes up in almost every conversation she has with teachers.

Struggling students either stay in the classroom where the entire class becomes distracted, or they are sent out of the classroom, which causes them to fall behind. Their grades and test scores suffer, and they begin a cycle that can lead to chronic absenteeism, or end in dropping out.

“The emotional toll it takes on a teacher when he or she is trying to balance that individual student and the rest of the students without the support of a social worker or counselor is huge,” Potter said.

Many times disruptive behaviors are tied to recent trauma, Kozlovsky said, “Trauma affects their ability to focus.” Kids may get misdiagnosed with a disorder when really they are just in a state of hyper-vigilance, relying on what psychologists call “fight or flight” responses.

A strong behavioral and mental health provider knows the difference between attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and trauma, said Will Francis with the National Association of Social Workers. How those issues are addressed can make all the difference in a student getting the help they need to make the most of their education.

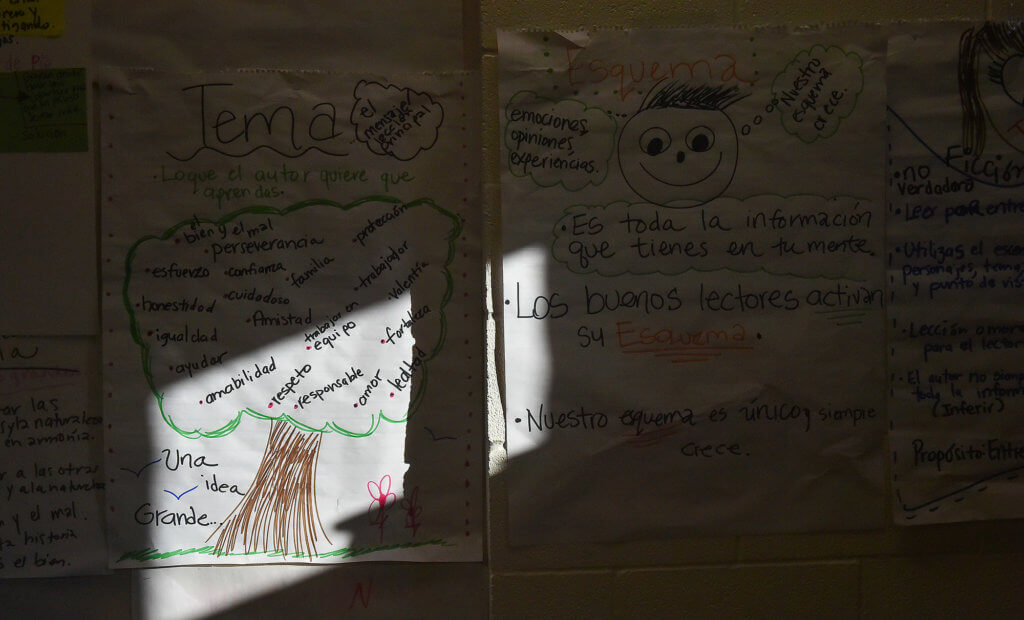

Studies show that wraparound services help bolster student performance. Robin Jerstad / Special to Folo Media

If it works, why not do it?

Where schools have invested in wraparound services, they have seen results. For the 2015-2016 school year, Communities in Schools of San Antonio reported that 93 percent of students they served had improved in behavior, academic performance or attendance — or in all three.

In 2014, Olmos failed to meet state accountability standards. Now it meets testing standards, and scores in the top 25 percent of schools in the state for gains made by low-income, minority, or English Language Learner populations. The wraparound services have been critical to those gains, Olmos Principal Gaila Booth said.

So why isn’t there a Lilliana Esparza or Valeria Kozlovsky on every campus?

Currently, the Texas Legislature does not adequately fund or facilitate additional support for public school children suffering from hunger, illness, emotional trauma, and other factors that might inhibit their ability to learn, said Woods, the Northside ISD superintendent.

“The whole notion of a system that lifts people up so that they can access education is lost,” Woods said.

Bernal filed a bill in the 85th Legislative Session, House Bill 353, which would have provided additional state aid to fund behavioral health professionals for high poverty schools. The bill died in committee.

As recently as 10 years ago, schools felt that wraparound services did not belong in public schools, said Josette Saxon, director of mental health policy at Texans Care for Children, a nonprofit policy organization focused on children. The Texas Education Agency had a “no more, no less” approach to education, she explained; and while the Legislature did address some mental health services, it did not connect them to schools.

Over time, the needs became harder to ignore, and they were manifesting more noticeably in schools. “We’ve seen it coming and we’ve had a little hood over our heads,” said Hierholzer, NEISD’s director of guidance.

Cyberbullying and natural disasters have added weight to a conversation on the many factors that can become barriers to a student’s education.

In the wake of Alamo Heights teenager David Molak’s death by suicide, the 85th Texas Legislature passed “David’s Law,”, which allows schools to enforce anti-bullying policies outside of school and increases the penalties for such behavior. After Hurricane Harvey, Gov. Greg Abbott formed the Hurricane Harvey Task Force on School Mental Health Supports to help children displaced by the hurricane.

While Saxon said that neither effort went far enough into the chronic trauma of poverty and preventative mental health supports for all students, she sees these developments as the beginning, not the end of the conversation. “We are increasingly recognizing that addressing the social and emotional health of all students is an important piece of providing an education,” Saxon said.

“The problem in Texas is that we have underfunded education for so long,” Francis said, and that general underfunding has made it difficult to ask for more money tied to specific educational issues.

Regardless of what the Legislature does or does not do, Esparza is confident that the local community’s generosity toward Olmos will continue. They feel an ownership and responsibility toward the students, she said.

Esparza’s own empathy for the students she serves comes from her personal faith, and how she grew up. “We didn’t have wealth, but we had a lot of richness,” she said. She remembers being sent with soup to an ailing neighbor, and her father, who himself struggled with mental health, telling her that people who are homeless should be treated as “brothers and sisters.”

“The little that he had, he would give it to whoever needed it,” Esparza said, adding that this kind of demonstrated empathy would improve every family’s encounter with the education system.

This article was originally published by the H.E. Butt Foundation’s Folo Media initiative in 2017.