In February, shortly after Dr. Colleen Bridger became the director of the Metropolitan Health District, District 4 Councilman Rey Saldaña approached her about making an “aggressive push” against sugary drinks. A month ago, Bridger appeared to begin the campaign by authoring an op-ed on the subject in The Rivard Report.

“[W]e have diluted the public’s understanding that drinking sugar is bad for you,” Bridger wrote. “It is bad for your brain, your teeth, your stomach, your weight, and if you have a chronic disease, it’s bad for that, too.”

Bridger’s opinion piece unearthed what had become a heated public health debate three years ago, which, at the time, raised questions about the soda industry’s role in San Antonio politics.

In May 2014, Bridger’s predecessor, Dr. Thomas Schlenker, presented data to the Council that showed a correlation between weight lost in San Antonio and decreased soda consumption. He also warned that the soda industry was targeting children, low-income communities and minority populations.

“Low-income adults consume twice the percentage of their daily calories from sugary drinks compared to higher-income individuals,” according to the Center for Science in the Public Interest.

Courtesy Bexar County

Bexar County Judge Nelson Wolff and Schlenker discussed the issue several times. Schlenker recalls Wolff saying, “If the city is going to drop the ball on this, then the county is going to pick it up.” The county eventually did so by distributing the advertising campaign the city chose not run.

“You wouldn’t feed your kids 16 packets of sugar. Why let them drink it?” one ad read.

“What some of the Council said was, ‘Well, wait, now (soda) isn’t the only culprit’,” Wolff told Folo Media recently. “Well, no. Of course, not. But it is part of the problem. The city gave in to the pressure from the industry.”

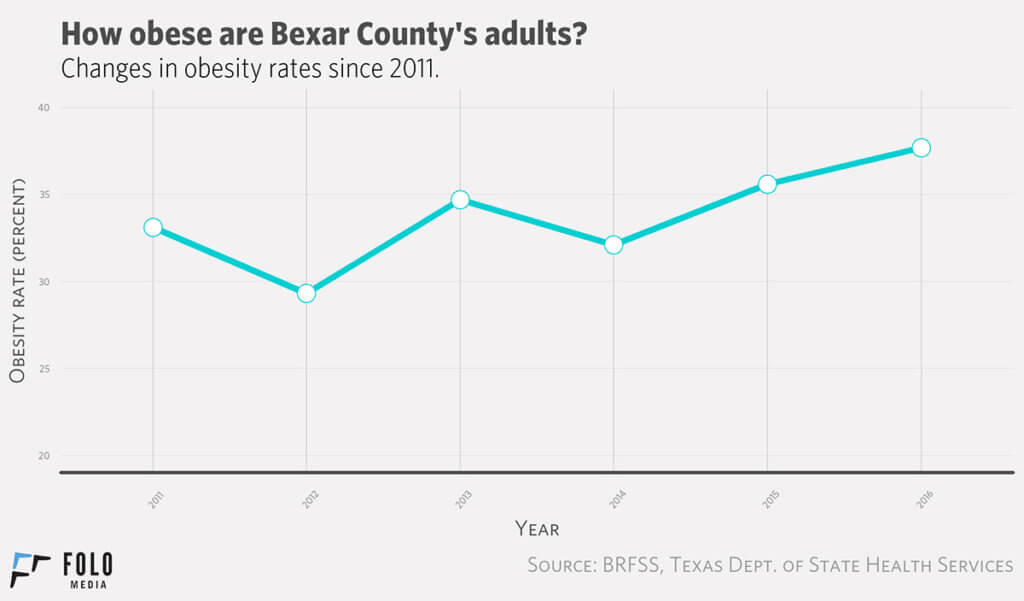

In 2014, Schlenker presented to the Council data showing that from 2010-2012 the obesity rate in San Antonio declined. The dip correlated with results from a survey that showed 80,000 Bexar County residents had stopped consuming soda. In 2009, the city received money from the Obama administration, which they began to use in 2010 to fund programs to target obesity, and the survey was a result of that funding.

But by 2014, San Antonio’s gains were lost. In that year, the Alamo City was ranked the second fattest major city in the nation by Gallup — 32.1 percent of the population was obese, according to data provided by Metro Health. As of 2016, 37.7 percent of the population was obese, according to the same data.

Schlenker did not ask the Council for money or to alienate soda entirely. He said he felt educating individuals on the effects of daily soda consumption would be a positive and measurable first step for the city to take.

Then-Mayor Julián Castro encouraged Schlenker to create a strategic plan for a campaign. However, the Council as a whole didn’t fully embrace Schlenker’s plan — for example, Ivy Taylor, District 2 Councilwoman at the time, asked that he broaden the campaign to include healthy foods.

Taylor and District 9 Councilman Joe Krier were the most critical.

Krier said he did not feel the city should get involved in individuals’ health choices. He felt like a campaign against soda would be a slippery slope into controlling other aspects of people’s health.

The Coca-Cola Co. North America Group and the American Beverage Foundation for a Healthy America gave the city at least $3.5 million in 2013, according to media reports at the time. This led both the public and the media to criticize the City Council and the City Manager’s office, which was overseeing Schlenker’s campaign development, for failing to act on the issue. Read more about the controversy and the role the City Manager’s office played in shutting down Schlenker’s committee here, here and here.

Schlenker presented on the issue to the Council again on April 1, 2015, but he mainly spoke about diabetes as a whole. By this time, Taylor had become mayor. Also by this time, the county had picked up the campaign in February and formed a committee to tackle the issue. Representatives from the coalition that were working on the county’s campaign asked the city for a resolution of support.

Wolff said the beverage industry began lobbying him as soon as he posted the vote for the County Commissioner’s court. Krier said he was not lobbied by the industry and added that it is not true that the industry had any role in the Council’s decision.

The Council did not grant a resolution of support.

“With Ivy (Taylor), I would say that no, it was not possible under her,” Schlenker said. “I think it was going forward with sort of, not full endorsement, but not opposition while Castro was in office.”

Folo Media was unable to contact Taylor for comment.

Where City Council stands on sugary drinks today

With a largely freshman City Council, a new mayor and new Metro Health director, the climate appears to have changed.

Five City Council members — Saldaña, Ana Sandoval, Roberto Treviño, Shirley Gonzales and John Courage — told Folo Media they would support an educational awareness campaign to inform the public about the dangers of consuming too many sugary drinks.

District 6 Councilman Greg Brockhouse is the only member who said he would not support a campaign. District 10 Councilman Clayton Perry and District 8’s Manny Pelaez declined to give a statement. District 3 Councilwoman Rebecca Viagran and District 2 Councilman William Shaw could not be reached for comment.

None of the City Council members Folo Media spoke with knew where Mayor Ron Nirenberg stood on the issue; the mayor’s office declined an interview, stating that Bridger would be Folo Media’s contact for this article. However, Saldaña, who served on the Council with Nirenberg in 2014 — when Schlenker first broached the subject — said the mayor was in favor of a campaign back then.

Brockhouse said it would be “absolutely ridiculous” to spend city money on an awareness campaign. He would not support a campaign, regardless of the cost, because he sees it as the first step in creating a tax on sugary beverages. He feels Bridger made it clear in her op-ed that her ultimate goal would be a tax on sugary beverages.

“At what point does the San Antonio Council stop telling people how to live their lives?” Brockhouse asked. “I think the Council is trying to change the way the world runs.”

The city would not be able to pass a tax, even if it wanted to, because of state law, Bridger said. In her op-ed, Bridger argues that there needs to be a tax, but she told Folo Media that Metro Health had several other health priorities to tackle before she would consider pushing for a tax — which would require a change in Texas law.

District 7 Councilwoman Ana Sandoval chairs the Community Health and Equity Committee. TOMAS GONZALEZ | SPECIAL TO FOLO MEDIA

Saldaña would be in favor of a tax if that was the best way to tackle the issue, but other Council members Folo Media spoke with said they either opposed it or felt a campaign would be more effective and plausible.

Sandoval, District 7 Councilwoman and chair of the Community Health and Equity Committee, said the Council will likely begin to tackle obesity — and sugary drinks — after it finishes its current health project, Tobacco 21, a campaign to change the minimum age to buy cigarettes from 18 to 21.

Sandoval said sugary drinks are one part of the obesity matrix the city can tackle through a “health equity lens,” along with food desserts and the way unhealthy food is marketed in low-income areas.

Bridger has not yet scheduled a time to present the issue to the City Council, but some on Council said they heard the discussion could happen as early as December or January.

“It’d be wonderful to have city resources on the sugary drink issue,” Wolff said, referring to the possible upcoming discussion. “That would be a big step forward in helping us get our message across.”

Editor’s note: Schlenker provided a press release from Feb. 25, 2014, detailing that the obesity rate decreased from 35.1 percent in 2010 to 28.5 in 2012. However, when Folo Media requested the obesity rate for the last 10 years, Metro Health warned that obesity rates after 2011 should not be compared with those in 2010, or prior years, because of a change in methodology.

This article was originally published by the H.E. Butt Foundation’s Folo Media initiative in 2017.