Pairs of seventeen-year-old boys stand and stare at each other, a foot or so of space between them. They landed in juvenile court, and a judge mandated that they enter this mentoring program called Rites of Passage, which is run by the San Antonio Fatherhood Campaign (SAFC).

Today’s rite of passage: help each other make decorative plaster face masks, using their own faces as molds. To do it, they’ll have to smear gobs of Vaseline on each other’s face, then fold down strips of gauze, gently following the curves and contours of one another’s skin.

Ramon Vasquez, the 56-year-old founder and executive director of SAFC, says this art exercise calls forth virtues of caring and reflection that exist in all men, but that get tamped down by machismo—a tough-acting culture of toxic masculinity.

“So imagine,” Vasquez says, “one young boy is about to apply Vaseline to this other guy’s face—and the things he has to overcome internally. ‘I actually have to touch this guy’s face in a very caressing way. Put these strips [of gauze] on this other guy’s face. And I’ve never touched another man’s face unless I’m hitting him.’ And then think about the other guy, who’s like, ‘This guy is gonna touch my face?’”

Do the boys resist this exercise? Every time. Do they try to bail? Of course. “But that’s why we have other men there” spread throughout the room, says Vasquez. “[To say:] No, it’s okay. We have to help them work through this.”

Some of these teens, Vasquez says, have never imagined living past their early 20s. They hail from neighborhoods where poverty is widespread and opportunities are limited. But at Rites of Passage, experiences like collaborative mask-making provoke for each boy new thoughts about who and what he really is—a sacred person.

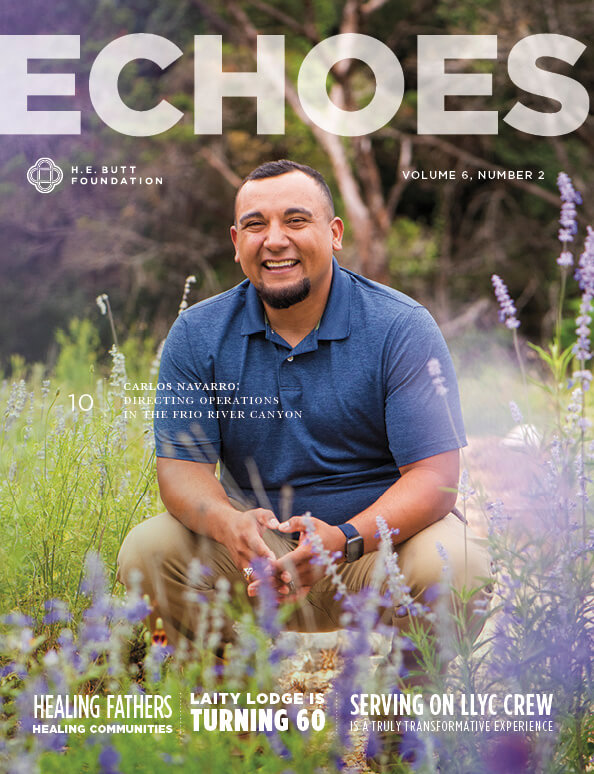

“They get to write on the inside of the mask how they are feeling inside. And [decorate] the outside of the mask how they want to be perceived by others,” says Vasquez.

“We tell them: you need to be the mirror. The inside needs to reflect the outside. And that’s what you work towards. That’s what we’ll help you do.”

Rites of Passage focuses on teens, but the lion’s share of SAFC’s work reaches adult men, especially those who have abandoned or hurt their families—or who are at risk of doing so.

Mark Johnson is 46-year-old father of four. Last year, soon after he lost his mom to COVID in August, his 22-year marriage began to fall apart. Around Thanksgiving, he and his wife had an altercation in front of their kids that led to the Department of Family and Protective Services getting involved. Johnson had always seen himself as a good dad—not a perfect dad, by any means, but a dad who loved his kids. Even so, he found himself holding a court order instructing him to attend a 9-week SAFC parenting class.

Johnson grew up tough himself—he describes an empty fridge, borrowed clothes, a mom who would leave to be with her family in Mexico for weeks on end, and a dad who was quick with his belt. Even so, the first time he logged into his court-mandated workshop earlier this year, he saw a bunch of men that, frankly, cowed him a bit.

“You can see the chip” on their shoulders, he said. “They do not want to be here. They grew up tough, with hard-a** dads. They give 2–3 word answers to questions.”

But the SAFC class is designed to puncture that veneer. As it opens, the facilitator starts by asking everyone to go around and name one positive thing and one negative thing that happened to them over the last week. And slow but sure, that simple question invites real answers.

The parenting class happens on a rotating schedule, so new members are joining in with other men who are further along—first-timers are hearing from men who are halfway through or who are “graduating”—attending their last class and sharing about what they’ve learned in the two-plus months of sessions.

As guys start sharing, says Johnson, “it starts breaking down your guard.”

The class Johnson took is one of a handful with names like “Raising Children with Pride,” “Healing Wounded Families,” and “Healing the Wounded Spirit.” Some are for men only and others are for moms and dads and whole families. SAFC also offers monthly “talking circles”—support groups for all kinds of men struggling with the pressures of family, work, or, well, just being a man. SAFC hosts major public events like the Father’s Day Fiesta, which in non-pandemic times attracts families from across the historic West Side. In addition, SAFC creates whole-family services, including a doula center for expectant parents and a diaper program that gave away 350,000 diapers to local families last year.

In all this work, SAFC draws on the deep cultural heritage of the region, summoning wisdom of ancient indigenous traditions—mask-making; elders as guides; attending to the sacredness of each person. SAFC draws on these traditions because they are effective—very effective according to a 2010 University of Texas study of SAFC. But the work is also culturally specific because SAFC was founded under the umbrella of a larger organization—American Indians in Texas at the Spanish Colonial Missions (AIT-SCM, a.k.a AIT).

AIT was founded in 1994 by descendants of the Tap Pilam Coahiltecan Nation, indigenous people who have lived in this region since well before Franciscan friars established missions in the 1700s. AIT exists to preserve and protect the culture of the tribes who preceded any European presence in this area, and has an array of programs ranging from Spanish missions tours to arts events to civic engagement to family health and wellness.

SAFC is an expression of AIT’s mission—here, restoring families and men is a way of preserving and protecting heritage. Historic practices and beliefs are woven seamlessly into classes and mentoring sessions. A recent training session opened with a traditional prayer and song. At the AIT headquarters, a wellness room invites staff to take breaks for drumming or holding silence. And consider the name of SAFC’s doula program—Seventh Generation Birth Services.

“It’s an American Indian concept,” Vasquez explains, “that the work we do and the decisions we make have to impact seven generations out. So if we think that way, then maybe we can understand the importance of the decisions we’re making today.” In similar fashion, Vasquez says that the report card on SAFC’s work is the children of the men they are working with today.

Greg Marshall, SAFC’s program director since 2014, says these cultural traditions help them remember that their healing work is holy work. “Sacred” is a term used often in SAFC conversations to honor the inherent holiness and dignity of all people.

And so fatherhood, in this view, is also sacred. “We don’t advocate for dads,” says Marshall. “We advocate for the sacredness of fatherhood.”

SAFC offers a full schedule of classes every day, plus 500-600 mentoring hours per month. On a recent Friday at SAFC’s offices in the West Side, two classes were happening online while another in-person class was underway and an afternoon training session was about to begin.

All of this work—this ongoing focus on fathers and men—makes SAFC unique in the nonprofit space. Vasquez cites a 2015 local study of gender-specific social services that found that while 51% of area nonprofits have programs targeting girls, only 3% have services for boys. “There’s still not a lot of people working with dads or males,” says Vasquez.

According to the most recent U.S. Census, 1 in 4 children live without a biological, step, or adoptive father in the home. Vasquez calls this absence “a public health crisis.” The National Fatherhood Initiative says that children who grow up without fathers face daunting odds: four times as likely to experience poverty, incarceration, abuse drugs and alcohol, and become teenage parents. They’re also more likely to repeat the pattern of their own childhood. SAFC’s internal surveys show them to be dealing with many men who are abuse survivors, men living with diagnosed mental illness, men who have been incarcerated at least once.

“Hurting people hurt people,” says Marshall, 53, who is a former client of SAFC himself. He was guided into the program in 2013, during a season of forced separation from his three children. Even as Marshall’s marriage ended, the restoration he experienced through SAFC’s classes and workshops made him want to devote all of his time to the cause.

Marshall says SAFC helped him “start seeing the woundedness in our communities. And I said, ‘I want better for my kids. I want my daughter to marry a good man. And what are we doing to inspire men to be good?’ So it really tied into my own sacred purpose.”

Between court referrals and the 15 percent of clients who find SAFC through a family member or on their own, “the demand is ridiculous,” says Vasquez.

And what, exactly, is driving all of this demand? For starters, economic hardships that have plagued families in these communities for decades.

“Financial struggles are often what tightens the screws,” says Marshall. Most of the men and youth clients of SAFC live in neighborhoods that were originally segregated along racial lines and have long been subject to public neglect—little development, insufficient housing and other infrastructure.

These men are carrying the weight of those injustices.

Another factor: “failed policies,” a phrase that comes up a lot among SAFC leadership. For instance, the policy that says single moms living with their kids in public housing can’t let the kids’ father move in with them if she wasn’t already married when she obtained her housing. So if dad moves in, the family loses its housing. “We’re dealing with a generation of children who grew up being told, You better not say your dad’s here. Your dad can’t be here,” says Vasquez. “Think of what that makes a kid believe about being a dad.”

“The policies are haunting us,” says Frank Castro, AIT’s program director, who has been associated with SAFC for most of its history. He says that men—either by their absence or by their behavior—are often regarded as the drivers of family and social ills. But SAFC encounters countless men who have been harmed by those very social ills, men who are the legacy of decisions made and cultures created well before their time.

Marshall says that one lawyer he spoke with guessed that of 10,000 cases that had come through family court, 6,000 of them were men with what he’d call “red flags”— “no life skills, coping skills, things like that.” These were not men who had committed domestic violence, but they had all the signs of men who do eventually commit acts of violence or abandon their families.

The problem is that there’s almost no support for such men. “What blows my mind is that we’re ready to invest so many dollars and resources at the end, by creating treatment centers or prisons…and to me that just doesn’t make sense,” says Vasquez.

Mark Johnson, the dad who recently finished his SAFC class, echoes something the SAFC leadership says all the time: “This is”—or can be—”preventative medicine.” Even though he was a decent dad before, “I needed [this] 20 years ago.”

He says the tools dads learn to use in the SAFC class are sneakily transformative. “Like, the 1-20 rule,” Johnson says. That’s the idea that whenever you get home from work, you should give each individual in the household 20 minutes of undivided time—checking in, asking about their day, listening. And you should also give yourself 20 minutes of undivided time—checking in with yourself, listening to how you feel about your day.

“For some guys, that’s a breakthrough,” says Johnson. “They come back to class the next week surprised by how much something like that means.”

He plans to stay involved with SAFC, and he’s hoping that other places will catch the drift of their work. “Churches, employers, organizations ought to be making this available,” he said. “You know a guy who works with you or goes to your church who is about to get married, or about to become a father? Send him to SAFC.”