Every Tuesday morning, Jack Elder washes dishes in a small white house on Nolan Street on San Antonio’s East Side. Sometimes he makes coffee or sets out pastries on a kitchen island cluttered with baking dishes and serving spoons.

In the backyard, around midday, Elder tends to rows of squash, tomatoes, carrots and other vegetables. He scoops composted coffee grounds and food scraps onto the rows. Not much is growing now because of the heat, but during much of the year the vegetable rows and fruit trees provide supplemental food. By late May, a few handfuls of carrots, a row of squash and several small, still-green tomatoes have started to grow. Elder bends slowly, as if the movement hurts the joints in his lanky limbs, to examine the produce.

For 30 years, Elder, 74, has done some variation of this routine at Catholic Worker House, a homeless center in Dignowity Hill, where he began volunteering in the late 1980s. Recently, the house has been serving meals to between 75 and 125 people twice every weekday.

Sometimes Elder makes small talk with the other volunteers or helps the visitors find cups and sugar for coffee, but most of the time he prefers to work in silence.

“[Jack] has been nothing but help and kindness since I’ve been here,” said John Meadows, one of the live-in volunteers at the Catholic Worker House. Laughing, he said, “He invites us to his Christmas party every year, no matter how drunk we get.”

“Jack was a serious activist in the ‘80s,” a man washing dishes says over the dull roar of the 100-plus people milling around the 1930s house and backyard while Elder and the other volunteers wash dishes.

Elder has a master’s in education with a concentration in Spanish and a bachelor’s degree in biology from Southwestern University—now Texas State University. He stays caught up on news, especially about social issues—immigration, in particular.

Throughout the course of several interviews Elder spoke about the flood of immigrants taken in by the Mennonite church in 2016, the city of San Antonio suing the state of Texas over SB 4, and current immigration policies.

The height of Elder’s activism was more than 30 years ago, but he still tries to draw attention to the current plight of immigrants.

“There is a long stretch of my life where I have done a lot, but I’m looking toward the future,” he said.

In the 1980s he was director of Casa Oscar Romero, a refugee shelter in the Rio Grande Valley. During this time he was arrested twice for transporting refugees from Central America.

He called the death of 10 immigrants in the back on an 18-wheeler on Sunday a “human travesty.”

He said immigrants will continue to die in inhumane conditions as they try to cross into the U.S. until government and citizens start to address the issues driving people out of their homelands.

“People are fleeing not just because they like the weather here,” Elder said, “their lives (in parts of Mexico and Central America) have become so untenable because of gang violence and the economy.”

Over several conversations in May and June, Elder was reticent to talk about himself, pointing toward a box overflowing with clips only to protest another profile being written about him.

“I’m not the story,” he said once. Later he added, “I just think enough has been written about me.”

In addition to his work with the homeless and food insecure, Elder volunteers with native plant and environmental organizations and serves as an alternate on the Alamo Area Metropolitan Planning Organization’s pedestrian advisory board.

“People ask ‘Jack, what do you do?’,” Elder says. “I basically just hang out in my backyard and stay involved in the community … Part of activism is just wanting it to be part of your life.”

Elder poses with his dog Pepper at his home in the Highland Park neighborhood. “We are growing old together,” he said. WENDI POOLE / SPECIAL TO FOLO MEDIA

Elder lives in a house on a quiet street in the southeast neighborhood of Highland Park. Some of the homes, built mainly in the 1920s and 1930s, are worn by the weather. Others have undergone recent facelifts as new families have begun to move in.

He moved to the neighborhood in 1979 because his mortgage was hundreds of dollars cheaper per month than what his friends in the north were paying. Elder, then a school teacher in Harlandale, one of San Antonio’s poorest school districts, could not afford to raise his five children and pay that much rent.

At the time, there was a lot of crime in the neighborhood. Many of the people living in the area were immigrants and had a difficult time stabilizing. Elder said he has always felt safe in his home. These days, there is still crime, and households struggle, but, slowly, gentrification is creeping in with brightly painted houses and well manicured lawns.

“My house got shot up in 1991, on accident,” Elder said. “They busted a few windows. One above the bed I was sleeping on. I was covered in glass. I remember waking up the next morning saying, ‘What a truly beautiful day.’”

Elder has fallen in love with his house, where he raised his children, and the neighborhood.

In his yard, he built a red and yellow wooden library box. On a recent day it held 11 books on various topics, with titles ranging from a murder mystery called “Dark Rivers of the Heart” to “The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing,” a contribution from someone in the neighborhood.

Elder says another neighbor stopped by to ask about the box. “He said, ‘I don’t read,’ and I told him that that was OK, that he should send his son over to get a book. The next day his son and grandson were in my yard reading.”

Besides working at the Catholic Worker House, Elder has volunteered with Meal on Wheels for the past six years.

Every Monday he attaches to his bicycle a plywood cart that reads “Car – 1” (one less car) and rides two miles to pick up about 16 meals. With his cart weighed down by the gallons of milk and food, Elder delivers food to his neighbors over a 4- to 5-mile route.

Elder and his son, Richard, outside of their home at Casa Romero, June 1984. COURTESY / JACK ELDER

In 1965, Elder’s life of service started when he joined the Peace Corps after earning a bachelor’s degree in biology from the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. He was sent to Costa Rica, where he worked on rural community development.

He met a health inspector—with whom he is still friends with today—and began developing clean sources of water and safe latrines for the community.

“I had no office,” Elder said. “I had no boss. I lived in a small room and I played soccer and hiked the hills.”

In 1967, Elder’s tour with the Peace Corps ended. He took a bus from Costa Rica to Panama, bought a motorcycle and journeyed for three months back to his home state of Connecticut.

After working for a few months doing odd jobs, he decided to head west on his motorcycle. In May 1968, the day before he was set to leave, the draft notice arrived.

“I realized that the Army was part of our foreign policy, too,” Elder said. “If the Peace Corps didn’t work out, then there was always the Army.”

He was seeing a woman, Diane Datz, who would later become his wife, but they decided to put off engagement until he returned from the war.

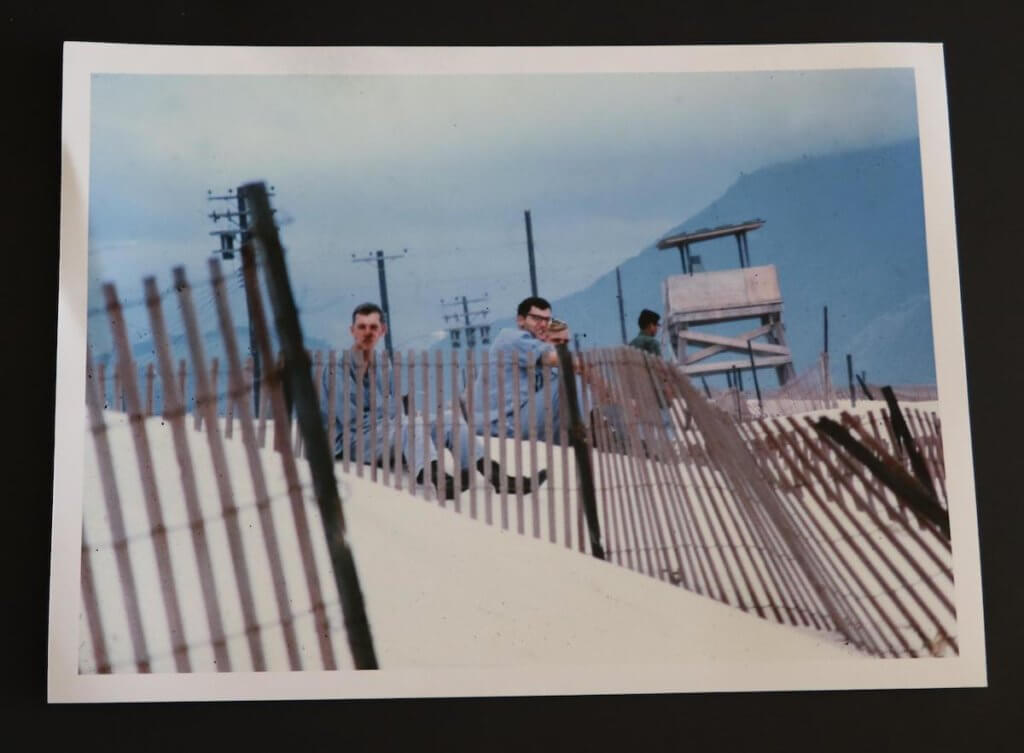

Elder took photos of his team mates on the beach while stationed in the guard tower. COURTESY JACK ELDER

While stationed in Vietnam, Elder became the resident phlebotomist for the American soldiers in the Cam Ranh base. He spent his days drawing and testing blood for common local diseases like hepatitis. Sometimes he was on guard duty and would keep watch on the coastal base he was stationed at from atop a guard tower, but he was never forced to take part in the fighting.

In 2011, Elder was diagnosed with Parkinson’s due to his exposure to Agent Orange.

Working with Central American refugees

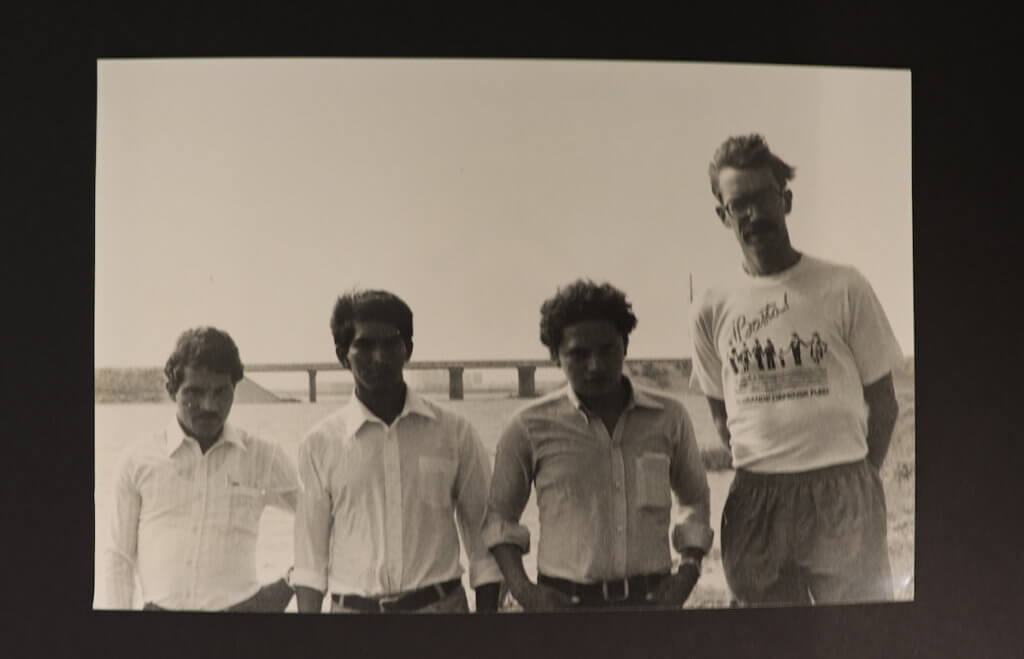

Elder and three refugees from El Salvador stand on the beach at Corpus Christi in Oct. 1984. COURTESY / JACK ELDER

In 1970, Elder left Vietnam and headed to New York, where he married Datz. They moved to Texas, where Elder earned a master’s degree in San Marcos before moving to San Antonio. He began teaching math at Leal Middle School on the Southside.

A few years later, in 1983, Datz asked him to move to San Benito and run Casa Oscar Romero, a refugee shelter in the valley sponsored by the Brownsville Roman Catholic Diocese.

The shelter took up about half a city block and consisted of an old building renovated to house immigrants; a trailer where Elder and his family lived; a community garden; a communal kitchen; an outdoor area for washing clothes.

About a dozen refugees arrived every week.

More than 2,000 people signed a battered notebook during his time there. The notebook is currently in traveling around the country, with an exhibit called Northern Triangle.

One night, Elder was approached by three Salvadoran refugees asking to be transported from San Benito to Harlingen—a 15-minute trip northwest of Casa Oscar Romero.

“I told them, ‘You are going to get caught,’” Elder said. But the men were anxious to move on.

Elder drove them to a bus station. On the way back to the shelter he passed a border patrol car heading toward the station. Later, the police arrived at Casa Oscar Romero and claimed they saw him drop off the refugees at the bus station, though Elder said that was impossible that the officers saw him.

“I was indicted,” Elder said. “I knew there was a warrant out for my arrest (for transporting the men), but I wasn’t going to turn myself in. I was going to stay and work at Casa Oscar Romero.”

Elder was arrested on the church grounds, bailed out, tried for transporting refugees and acquitted.

Elder in handcuffs after he was arrested the first time. COURTESY PHOTO / JOE HERMOSA

Several months later, Elder was arrested again—this time authorities said he was transporting a Salvadoran family to a bus station. Elder denied that neither he nor Stacey Merkt, a volunteer from Casa Romero, who was also arrested, had anything to do with moving the family.

Elder faced a maximum fine of $21,000 and 30 years probation for six felony charges related to transporting immigrants that had entered the country illegally. While awaiting trial, he spoke publicly about his views on the importance of assisting refugees and the government’s role in unrest in Central America.

The Migration Policy Institute estimated that between 1981-1990, almost 1 million refugees fled from civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala. Until 1984, the approval rate for Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees seeking asylum in the U.S. was less than 3 percent, despite drastically higher approval rating for Iranian, Afghan, Polish and Chinese immigrants.

Elder became entangled in this outpouring of refugees at Casa Oscar Romero as part of the Sanctuary Movement—a grassroots campaign that started in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s—in which churches and other faith-based communities sheltered refugees in violation of federal law.

The movement winded down after the U.S. government began providing asylum for more Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees, however the movement has been reborn in the face of current day immigration issues.

Local churches in South Texas and San Antonio are still providing safe passage and transport for refugees, Elder said. In December, Elder assisted the San Antonio Mennonite Church which took in at least 500 refugees that had fled Central America.

When Elder spoke about the 10 immigrants who died, he sounded like he was back up at the pulpit of a local church, urging people to understand the reasons refugees seek asylum so that everyday people and policy makers can be more sympathetic to their plight.

Elder made national headlines as his trial played out. The media attention earned him supporters around the country.

In early 1985, Elder was convicted on six charges related to transporting immigrants who entered the country illegally.

U.S. District Judge Filemon Vela sentenced Elder to two years probation, during which

he was explicitly forbidden from helping refugees or publicly discussing immigration issues. Elder called the gag order “unacceptable” and refused the sentence.

The judge advised Elder to return to court in a week for another sentence. When Elder returned, Vela sentenced him to 150 days in the Halfway House in San Antonio.

The light sentence, the judge said, was because he admired Elder’s motivation.

“I agree with the ends of the sanctuary movement,” Vela said, according to a 1985 Chicago Tribune article. Though he felt he had to uphold the law and sentence, the judge told Elder, “You’re a good man.”

When Elder became director of Casa Oscar Romero in 1983, he intended to stay for one year. But he stayed a second, with his term expiring in August 1985. Elder believes the judge scheduled his sentence to end just after his contract expired on purpose to be merciful.

When Elder arrived to the Halfway House, then located just behind the main branch of the San Antonio public library downtown, he was greeted by supporters—though he would later receive a few pieces of hate mail.

Elder received a lot of support for his work with refugees, but not everyone want happy with him. He received many angry letters without return addresses while he was in the Half Way House. COURTESY / JACK ELDER

“Go back to Mexico,” one letter read.

Elder admits he was not a “model prisoner.” He walked around in a “Question Authority” shirt.

He had to follow strict rules about where he could go and when, lest he speak out and start a riot or revolution. There was one exception: he could attend any church he wanted.

Elder used this opportunity to begin volunteering at the Catholic Worker House.

Feb. 21, 1985, Elder was convicted on six charges related to conspiracy and illegal transportation of immigrants.

Elder lives a quite life now, but signs of his continued interest in social justice issues are scattered throughout his home. WENDI POOLE / SPECIAL TO FOLO MEDIA

After he was released, Elder took on odd jobs in fields such as construction and safety engineering.

Eventually, he returned to teaching at Leal Middle School. During his time, a Levi’s factory, which employed many of his students’ mothers, closed and moved to Central America.

About 1,150 workers were laid off in an already “economically marginalized community.” Elder said women were left scrambling to find a way to feed their families.

Elder did not know the community well enough to attest to the exact effect the loss of the Levi’s factory had on the community. However, he recalled telling a coworker that low math scores were likely due to the need for jobs. Children in his math classes were living in distressed households, which made it hard for them to focus on education.

Eventually, Elder left the school system. He applied for a tutoring position years later, some time after 9/11, but was informed they would be unable to hire him because of his felony record. He had taught after his conviction, with no issue, but after 9/11 he felt security across the country had tightened and his record was now a hinderance.

Ultimately, his choice to work with Central American refugees and stand up for his beliefs cost him his career in education.

Elder is content now, living with Pepper—a black lab mix with a graying muzzle that Elder rescued from a local park nine years ago. He enjoys volunteering and walking with Pepper in the park and riding his bike. Elder says his Parkinson’s is well managed.

At the Catholic Worker House, he maintains the gardens and helps out in the kitchen, like he has done for the past three decades, without complaint or signs of slowing down. Activity, he said, is like medicine.

“I look forward each day to working in the garden or going on a bike ride,” Elder said.

Elder still helps refugees and immigrants whenever he has a chance. During the flood of Central American refugees in December, Elder was on call night and day to pick up refugees and transport them to bus stations or airports.

A friend said to Elder recently, “Maybe we don’t need a great country, maybe we just need a good country.”

“I said, ‘Well if you look at how I’m living, I think I am living a good life’,” Elder said. “It might not be a great life, but I am very happy here, in this house, with my friends and my activities.”

This article was originally published by the H.E. Butt Foundation’s Folo Media initiative in 2017.