This article was originally published by the H.E. Butt Foundation’s Folo Media initiative in partnership with The Texas Tribune in 2017.

By Alexa Ura and Annie Daniel

On the economic front, 2016 was a year of modest improvements for Texas residents. Incomes continued to creep up. Overall poverty slightly dipped. The share of poor children in some areas of the state with the highest rates of child poverty dropped.

But U.S. Census estimates released Thursday also underlined a familiar narrative of income inequality within the state’s borders: Some Texans of color continue to be left behind when it comes to economic improvement.

The median household income in Texas last year hit $56,565 — up almost 2 percent from 2015. That’s fairly close to the national figure but still puts Texas behind 24 other states with higher median household incomes.

In 2016, median household incomes increased for all of the state’s major racial and ethnic groups. Household incomes for white and Asian Texans — at $70,131 and $82,081, respectively — easily surpassed the state figure. But black and Hispanic households, whose median household incomes don’t cross the $45,000 line, still bring home less money.

Despite a sharp drop in poverty in 2015, the state’s overall decline in poverty — down to 15.6 percent in 2016 compared with 15.9 percent in 2015 — was much more modest this year. That still translated to a few thousand fewer Texans classified as poor in 2016.

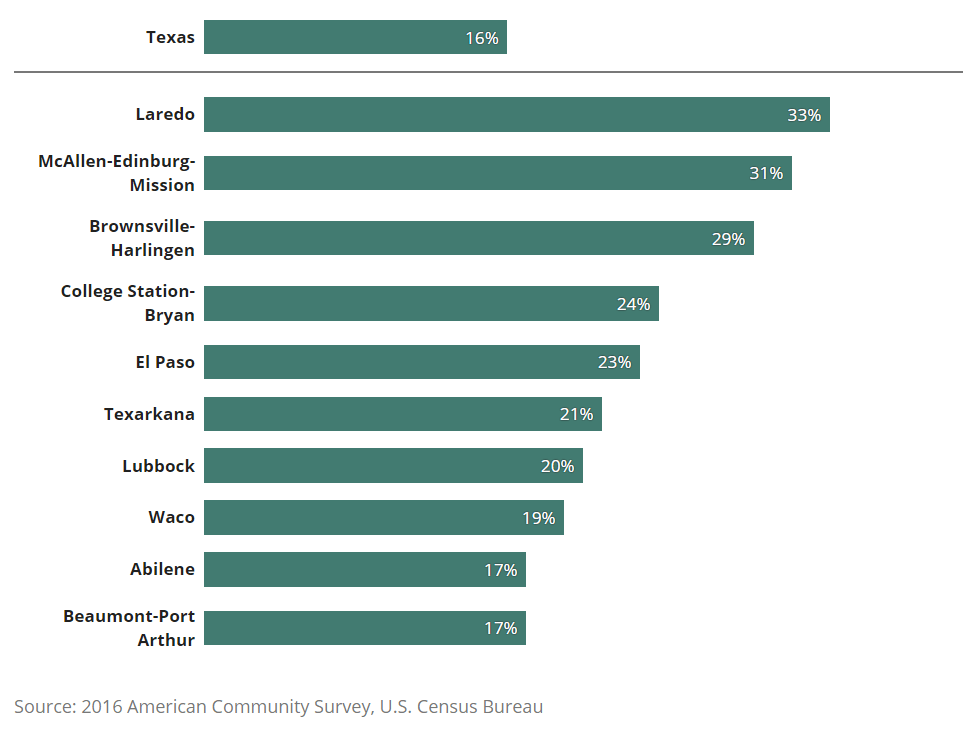

But the share of people living in poverty in half of the state’s 25 metro areas surpassed the state figure, and roughly half of the state’s metro areas saw increased poverty rates in 2016.

The census determines poverty based on income and family size. For example, an individual is classified as living in poverty if he or she makes less than $12,228 a year. A family of four with two children would be classified as poor if its income is less than $24,339.

Poverty in some South Texas metro areas, which are home to predominantly Hispanic communities, was roughly double the state figure. Those areas — where roughly one in three residents live in poverty — have for years remained among the poorest areas of the state.

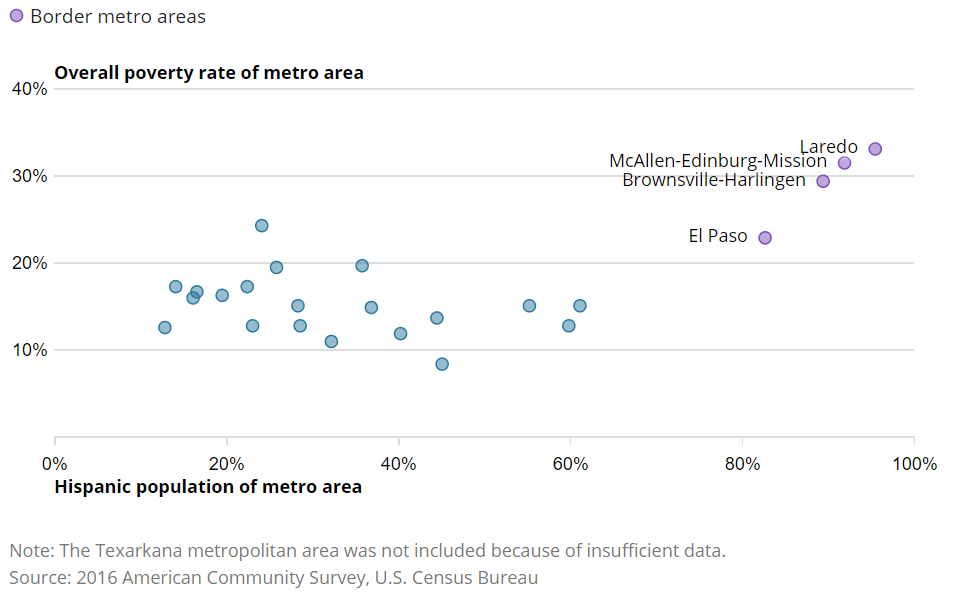

In fact, metro areas with high shares of Hispanic residents also tend to claim some of the highest shares of poverty.

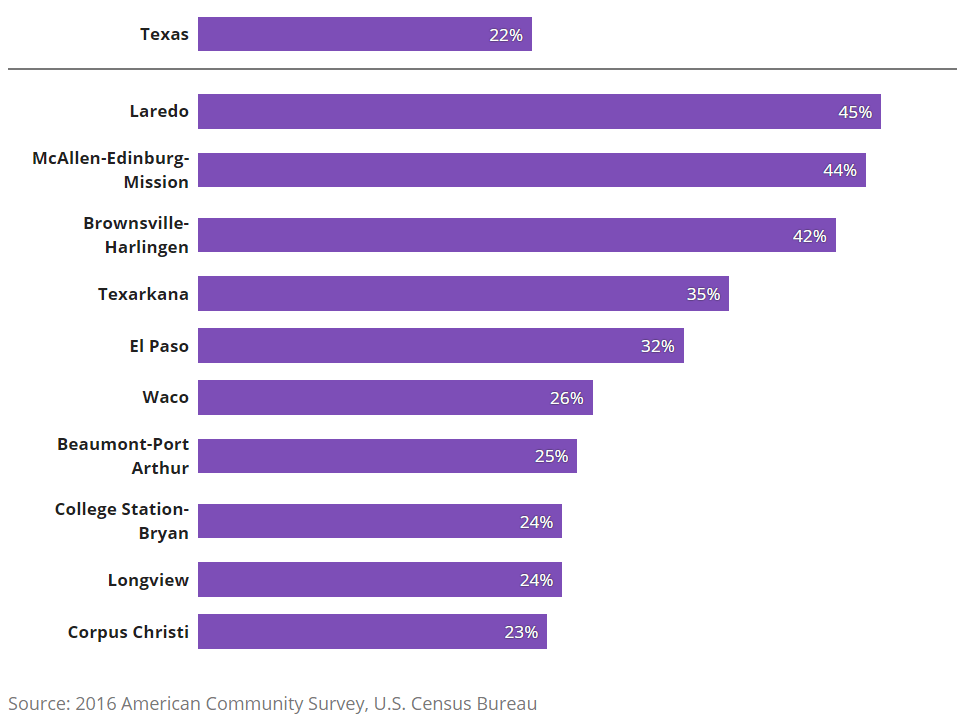

While the state’s overall share of children in poverty also slightly dropped, child poverty rates ticked up in 11 of the state’s 25 metro areas, and rates in 10 metro areas surpassed the state average.

Southern Texas also continued to be home to the highest shares of poor children. Children in the Brownsville and McAllen area live in poverty at almost twice the rate of the state overall. In Laredo, which had the highest share, 45 percent of children live in poverty.

The state’s economic disparities are also not limited to race and geography. Despite continued overall economic improvement, the wage gap between women and men and Texas barely budged.

In 2016, women who worked full-time, year-round jobs in Texas were paid 79.4 percent of what men were paid — an increase of half a percentage point from 2015. It’s a disparity that still translates to about $10,000 less in median earnings for women compared with men, and it has held mostly steady for several years.

The Texas Tribune is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans – and engages with them – about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues. See their work at texastribune.org