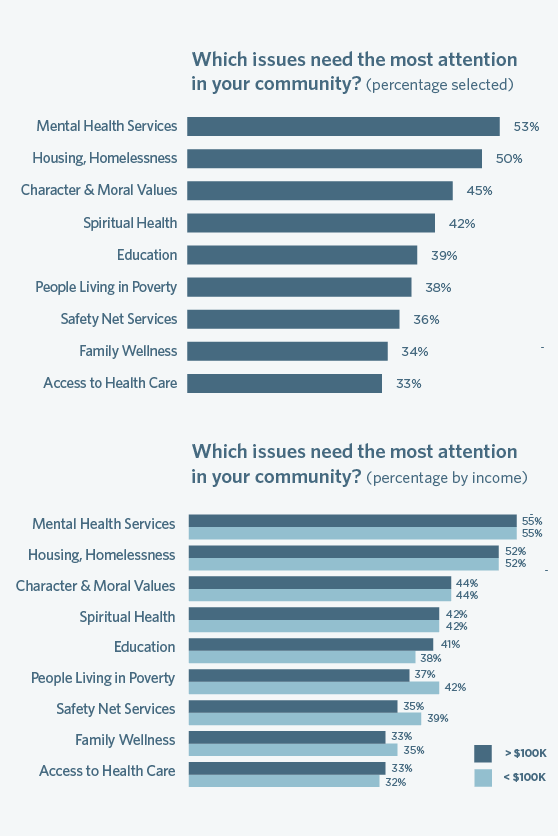

The survey opened with general questions about what social concerns people feel need the most attention. We also gave them a chance to tell us about what they’re already doing in their community.

Mental health and housing/homelessness led the way. Other poverty-related issues—the safety net, education, access to health care—fell a bit lower. One trend we saw was that higher-wealth households were less likely than households making less than $100,000 to emphasize issues like people living in poverty and a strong safety net.

Respondents left copious comments in this part of the survey, and a recurring theme was the fraying of the overall social fabric. “Lack of charity in public discourse,” said one respondent. “How polarized we all are. So sad,” said another.

Comments like these reflect a longing to build bridges across our social differences and conflicts. Some version of the term “polarization” appeared again and again, bemoaning a lack of understanding and unity between individuals and groups in our overall culture. Why are we so fractured? Why do we lack understanding and unity? Because we don’t know each other.

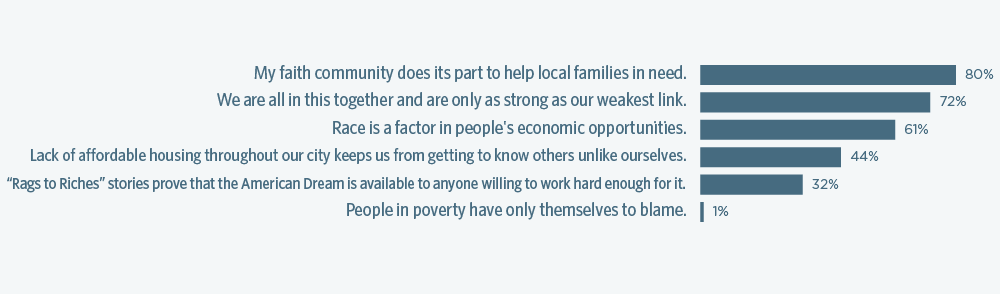

Opinions About Poverty — Do you agree or disagree with the following statements? (percentage who agree only)

As the survey developed, it became more specifically focused on poverty and inequity. Questions were designed to gauge how respondents view the economic and opportunity gaps between neighborhoods in their community.

The results suggest that, by and large, respondents hold complex views on how people become poor. They recognize that poverty is not simply a matter of poor choices, laziness, or even broken families. They see that poverty attacks people unfairly, and that it is a difficult problem to address because it is systemic, not just a matter of individual behavior.

They also suggested that poverty is not just other people’s problem. Seventy-two percent agreed with the statement: “We are all in this together and are only as strong as our weakest link.”

More than half (61 percent) acknowledged that “race is a factor in people’s economic opportunities,” while only one percent affirmed that “people in poverty have only themselves to blame.”

Yet within the 61 percent, there are significant differences by age and residence. Those who are under 50 years old and those living in Austin, Houston, and the DFW metros are far more likely to agree with the view that people in poverty make themselves poor.

Overall, one of the strongest opinions on poverty that emerged in the survey (affirmed by 80 percent of respondents) was “my faith community does its part to help local families in need.”

One way to read this finding is that people feel their faith community does not need to do any more than it is already doing. Yet many of the verbatims belie that reading: “No one does enough. Doing one’s ‘part’ is misleading—no one does enough so I guess I disagree even though our church does a lot.”

The survey shows the people affiliated with the H. E. Butt Foundation are aware of poverty, think of it as a priority issue, and see it as a complex phenomenon that traps people.

So how are they responding? Mostly by giving money and affirming and supporting the outreach ministries of their churches.

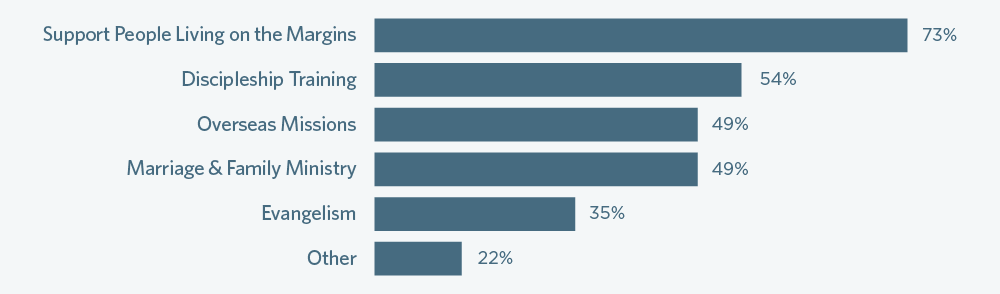

Church outreach comes up a lot in the survey. People were given a chance to prioritize their church’s various ministries—evangelization, discipleship, Bible study, and so on. Interestingly, respondents suggested that the work their church does to help struggling people is a higher priority than other traditional priorities.

Of course, when it comes to large-scale problems of poverty and inequity, giving money from a distance, or affirming your church’s outreach ministry, is not enough. It’s not enough from a Christian perspective, and it’s not enough to create real change.

Plenty of the survey respondents know this as well.

Some who think their churches are taking real action to address poverty also added their own laments, such as “we could do more,” “we can do so much more,” or “needs to do more and is headed in that direction.” These comments suggest an awareness of the difficulties of addressing poverty. “I know a lot of good people are doing what they can,” one wrote. “It just seems like we can never get ahead. Like emptying a swimming pool with a spoon.”

Perhaps people want to do more to address poverty, but they feel overwhelmed by the task.

Church Priorities — Places of worship tend to emphasize some priorities over others. Which of these initiatives (below) are top priorities for your church or parish?

One question in the survey was simply, “What are the words you live by?” While that may seem like a strange question for a survey on poverty and inequity, we wanted to see how people connected these issues to their deepest convictions and to the resources they turn to for direction and consolation.

Many respondents simply listed “Bible,” “Scripture,” or “Prayer.” Some mentioned “Daily Bible readings,” “Daily scripture reading and meditation,” “Daily prayers and devotionals,” or “Daily word” as critical for their day-to-day lives.

But some respondents offered more specific answers, and many of those answers were inflected with concern for people experiencing poverty. Among the most frequently mentioned scripture references by chapter and verse were the following:

Micah 6:8—“He has told you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you, but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God.”

Matthew 25:40—“And the king will answer them, ‘Truly I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.’”

The biblical mandate to care for vulnerable members of the community is a huge part of what it means to be a Christian. Micah 6:8 entreats us to “do justice” and Matthew 25:40 exhorts us to serve “the least of these my brothers.” Many of our survey respondents know these scriptures and hear their call.

But more common than any of the verses mentioned by chapter and verse were paraphrases of two other scripture passages: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” (Matthew 7:12; Luke 6:31) and “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your mind … and you shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Matthew 22:37-39; Mark 12:30-31; Luke 10:27).

“Do unto others…” “Love your neighbor…” What does it mean to live by these words? What kinds of relationships do these words call us into?

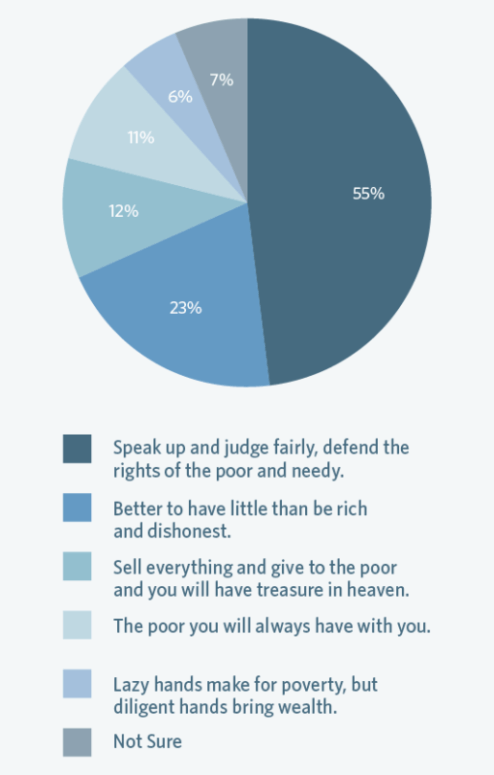

Preferred Bible Verses — One survey question asked people to choose one of five verses that might be said to reflect the Bible’s overall teaching on the poor.

Only six percent selected a verse that seems to lay responsibility for poverty directly on the individual: “Lazy hands make for poverty, but diligent hands bring wealth” (Proverbs 10:4).

Only six percent selected a verse that seems to lay responsibility for poverty directly on the individual: “Lazy hands make for poverty, but diligent hands bring wealth” (Proverbs 10:4).

A majority of respondents chose “Speak up and judge fairly; defend the rights of the poor and needy” (Proverbs 31:9). That’s a fascinating choice, because the verse reminds us that poverty is about power—who has it, and who doesn’t. Those who have high status are meant to advocate for those who lack status.

Many respondents wrote out additional verses in this section:

‣ “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

‣ “Love your neighbor as yourself.”

‣ “Do unto the least of these.”

‣ “Do justice and love kindness.”

These are verses of empathy and verses of action. If this is the Bible’s teaching on poverty, it’s calling us into relationship with others, calling us into neighboring.

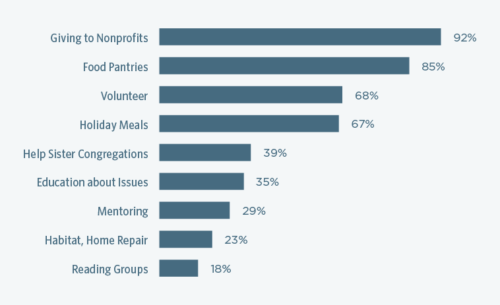

Initiatives — Here are some initiatives which encourage people to meet and serve neighbors from the parts of town they may not normally see. Which are you presently doing and/or appeal to you?

Overall, 92 percent of respondents report “giving money to a local nonprofit” as a current practice they undertake “to meet and serve neighbors from parts of town they may not normally see.”

In a similar vein, 85 percent are “giving food or money to food pantries.” These extremely high rates indicate that respondents are comfortable helping with their purses. Strong majorities also report volunteering for community organizations or sharing holiday meals and gifts.

But for the activity requiring the heaviest investment of personal presence—“mentoring at-risk youth”—only 29 percent reported current participation.

This insight does not mean to indict anyone for not already having a practice of being in relationship with people experiencing poverty. Our world is designed to limit such relationships in all sorts of ways and for all sorts of reasons. Remember, studies show that the most powerful determining factor in someone’s overall lifetime achievements is the ZIP code of their birth. The reason that’s true is that poverty is heavily concentrated within geographic zones—and so is affluence. In many cities today, people with plentiful resources rarely come into contact at all with people experiencing poverty.

No wonder the world feels so polarized.

So what is this community survey telling us? What are we hearing from these responses? In sum, the survey reveals a challenging set of realities:

About this time last year, we sent you a community survey. That was our way of starting a conversation with you about the gaps that exist within our communities, especially the gaps in opportunities and resources that leave so many families and children struggling to survive.

As a solution to a big social problem like inequity, “relationships” may sound too simple or too soft. But lack of connection between people perpetuates a lack of empathy and understanding, which leads to a lack of vision for lasting change. And there’s nothing soft about relationships.

Who received and responded to the survey? The basic answer: older people of Christian faith in Texas who tend to have an abundance of resources. These mature, affluent, religious communities see themselves as oriented to the needs of people experiencing poverty in their areas.