I come from a family of migrant workers who worked in the fields of the Texas Panhandle for generations. The moment I turned 16, I begged a manager at Long John Silver’s to hire me in order to escape the fate of all my cousins who had to work in those fields. Fast food was my “step up.”

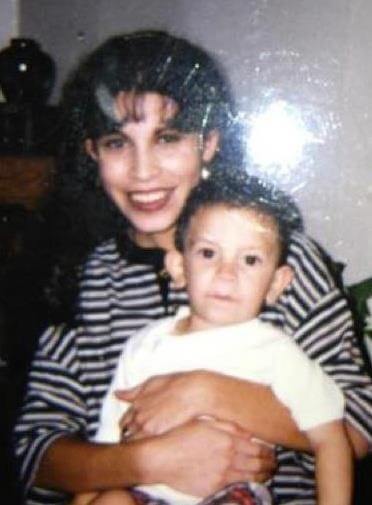

A few months into that job, I took a pregnancy test in the bathroom and found out that I was pregnant. I was a sophomore in high school. People suggested I get an abortion as a “solution” to my “problem.” I refused. In July of 1994, my first son was born. I named him Anthony.

Keeping him was an act of pure rebellion. I rebelled against the idea that I could not be a mother and that my child had no chance in life to be successful. I rebelled against the narrative that teenage mothers do not have what it takes to love fiercely. The women in my family were poor, but they were also brave, strong and hopeful in the face of seemingly hopeless situations. I wanted to be like them.

I was handed pamphlets by counselors in school and in clinics about all my “options.” They laid out the stats on how many “criminals” were born to teenage mothers and how the poverty rate for teen moms was so high. I didn’t even know what “poverty” was. To me, being poor was just the struggle. Everyone around me was also living in that same struggle. They also never told me about any options where I could get an education and raise my baby to be a healthy member of society.

Taking care of my son became my first priority. It came with a lot of mistakes because there were so many things my family and I did not know. What my family was good at was knowing how to survive as migrant workers. I did not want that life for me or my child. I wanted the American Dream. In my mind, that meant having a husband, a college degree, a house on the “rich side of town”—what I’d later came to know as the suburbs—and more children.

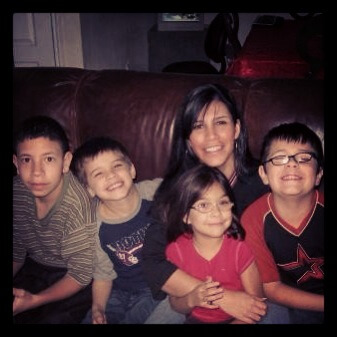

Anthony’s biological father was out of the picture. When he was three years old, I married the man he considered his dad and soon got pregnant four more times, one ending in a miscarrage around 20 weeks. My husband struggled with drug addiction throughout our eleven-year marriage. My mother helped me by taking care of my kids while I worked, but emotionally and financially, I was on my own.

People have asked me several times why I kept having kids while living in poverty. My answer is simple: I had no idea this was “poverty.” I was just working to keep my head above water and get to the next accomplishment. As far as I knew, this was the way to the American dream. I just had to pursue that dream as a mother with a GED, no financial literacy, a legacy of generational poverty, and a marriage with a man struggling with drug addiction.

After my fourth child, I had my tubes tied, following the advice of everyone who said having kids was irresponsible. I cried all the way to the operating room.

Not having more kids did not help my husband get sober. Not having more kids did not lift me out of poverty or give me access to education, healthcare, or a job that paid me a living wage. There were a lot of obstacles keeping me from those things, but my children were never to blame. My children were the reason that I got up every morning and kept fighting to create a life where I could get those things.

When I was 32 years old, a woman named Tammy became my mentor. She encouraged me to think about going back to school, and she walked me through the process of applying to Austin Community College. Around this time, I also became Catholic. For the first time in my life, I had people cheering me on and helping me correct mistakes as I made them.

My second husband and I were married in the Catholic Church. We bought a home in the suburbs of Austin and began to build a community. That community has walked with us through addiction, trauma, and ongoing financial hardship. They have held us up and paid for groceries and electricity when times were difficult. They’ve done all this without judgement. They taught us what it means to be cared for and supported.

Three years ago, Anthony took his life by hanging himself in my garage on a beautiful Wednesday afternoon around 2:25 p.m. His last words were, “I love you, Mom.”

Anthony’s suicide was the worst thing I have ever had to live through. Had I still been living with no support system, I would not have survived it.

There is so much space between me deciding to not have an abortion and Anthony’s suicide. That is another story and one I will share, but what I’m saying here is this: he was not destined to be a statistic just because he was born to a teenage mother and into generational poverty. He did not become a criminal. He graduated from high school and grew into a good man. He was a hard worker, polite, responsible. He was a devoted father to his two children. He had a mother who brought him and his siblings into this world because she loved them and worked hard to teach them the things she did not know.

Today, my grandchildren—Anthony’s kids—know something else I never knew: that they are worthy of the support and love we have from the people around us. I want that to be the story of every child’s life, regardless of the circumstances they are born into.

| Leticia Ochoa Adams is a wife, mother and grandmother who lives in Texas. As a freelance writer, she has contributed to The Catholic Hipster Handbook (Ave Maria Press) and Patrick Madrid’s Surprised by Truth (Sophia Press). Her work has appeared in numerous print and online publications including Our Sunday Visitor and Aleteia. Leticia was also a regular featured guest on the Jen Fulwiler Show on Sirius XM, and a sought after panelist at conferences, having most recently participated at FemCatholic and the Fall Conference at the deNicola Center for Ethics and Culture at the University of Notre Dame. Her website is leticiaoadams.com. |  |

It wasn't until Leticia became a mother that she realized how much stress was involved in living in poverty.

How a budding partnership with the Family Independence Initiative is helping families survive on their own terms.