Editor’s Note: This is the first part of our report on San Antonio’s summer hunger crisis.

Part 2: Going to where the hunger is

One afternoon in mid-June, I sat in a scrum of print journalists, photographers, and television crews at a press conference. With San Antonio Spurs coach Gregg Popovich at his side, San Antonio Food Bank President Eric Cooper announced that the need for summer food had doubled. Popovich called childhood summer hunger — which affects 238,064 children in Bexar County — “disgusting,” and said it was every citizen’s responsibility to address the need.

The press conference did its job: virtually all local San Antonio news outlets carried the story, as did NBA.com. We did, too. As of the end of July, the Food Bank had secured funding for 7.1 million of the 9 million meals it estimated would be needed throughout the summer.

But I couldn’t shake the story after I filed it.

The press conference had been short. Only a handful of questions were asked afterward. I had been researching summer hunger long enough to know many of the news organizations there had written about summer hunger for the past several years. Yet there was not much discussion about why the Food Bank was seeing double the need.

After the conference, I asked Eric Cooper what was driving the increased need — slightly worried I was missing something obvious.

Eric Cooper said it had to do with an increased awareness about the Food Bank’s resources, an increased number of sites the Food Bank served, and a change in the school district’s summer feeding schedules.

That helped, but I wanted to understand how districts had the power to so greatly affect the number of hungry children just by changing their schedules, and whether a summer hunger crisis was growing.

I requested data from the Texas Department of Agriculture, which oversees the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) and the National School Lunch Program’s Seamless Summer Operation (SSO) — two federal programs that reimburse schools and other organizations for meals they feed children in economically distressed areas during the summer — to attempt to answer these questions.

(Note: The summer nutrition programs fund most summer sites. However, not all sites/programs are funded by them. For example, if a church used its own money to serve food, their numbers would not be included in any of the analysis below. The Food Bank has sites that are federally funded, but many of the meals they give out are not. Not all of the 9 million meals the Food Banks hope to serve will go to children, or even within Bexar County.)

What emerges from that data — along with analysis of information from the Washington, D.C.-based Food Research Action Center (FRAC) and a series of interviews with school district personnel — is a complex picture of why so many kids in San Antonio spend summers hungry.

At the time of the press conference, there were 406 federally funded sites serving food to children across Bexar County. As of the publication of this article, there are only 103 sites.

For some students, next week they will return to class, after what was likely the hungriest week of the summer for them. Others will have to wait 1-to-2 more weeks before school starts and they have reliable access to food.

Below are some of my other findings.

In 2016, there were 238,064 children enrolled in the free or reduced lunch program. The term “economically disadvantaged” refers to the children receiving free or reduced breakfast and lunch during the school year.

Two types of federally-funded summer nutrition programs provide reimbursement for meals served at designed summer feeding sites.

To be eligible, a site must be located in an area where 50 percent or more households are economically disadvantaged. Both schools and nonprofits can operate sites.

The government reimburses the sponsoring agencies — including school districts and nonprofits — somewhere between $2- $4 per meal depending on factors like the location of the site and which of the two programs the site is participating in.

Any child younger than 18 can receive free food at any “open” site, regardless of their family’s income or where they attend school. Most sites are open, but a few are “closed” — meaning they only serve children that are registered.

According to FRAC’s 2016 summer report, 15 of every 100 children that participate in the National School Lunch Program — commonly referred to as “free and reduced lunch” — receive lunch during the summer nationally. In Texas, the ratio is 8.1 to 100.

Texas is ranked 48th out of 50 states and the District of Columbia for the percentage of economically distressed children that receive summer meals. The District of Columbia held the top spot with 48 children receiving summer meals for every 100 economically disadvantaged child during the summer.

There is no obvious single reason why more children would turn out this summer than last, just like there is no one, single reason why fewer children have been served over the past few summers.

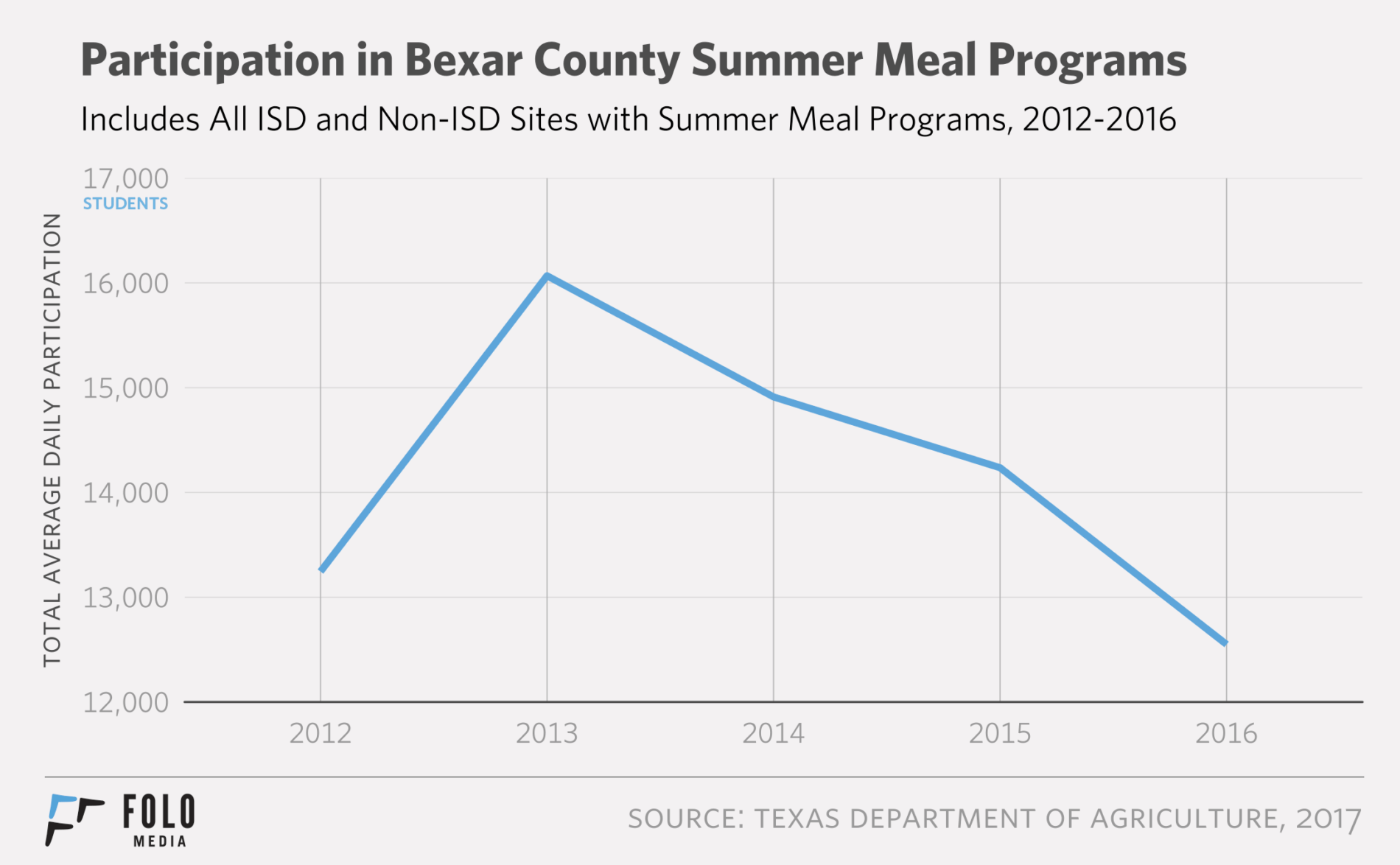

For the past four years in Texas, there has been a steady decrease in the number of children that receive food through summer nutrition sites and a slight increase in the number of children that need food — the number of children that received free and reduced lunch during the school year.

From 2015 to 2016, there was a 20.3 percent drop in participation in the programs in Texas. The year before, there was a 10.3 percent drop.

In sum, the number of hungry children is increasing, while the number of meals served through the programs are decreasing, both statewide and locally.

It is too early to say for sure, but it is possible that the extra need the Food Bank is seeing means children that have been previously underserved are now accessing Food Bank resources. Many districts Folo Media spoke with also reported seeing sustained or increased demand for food at their sites.

One possible reason for the yearly decrease: Fewer agencies are registering to sponsor meals and fewer sites are open each summer.

There was a 6 percent drop in the number of sites that were serving around the state in 2016, and a 6.4 percent drop the year before.

This trend holds true for Bexar County. In 2013, there were 31 agencies in Bexar County registered with the Texas Department of Agriculture; by 2016, that number had trickled down to 21.

Another reason the numbers are dropping: Data shows sites in Texas are feeding for a shorter time period.

In 2016 in Texas, there was a 17.4 percent decrease in meals served in July and a 9.4 percent decrease in meals served in August. In 2015, there was a 13.5 percent decrease in June, a 20.3 percent decrease in July, and 28.5 percent decrease in August.

It is unclear why sites are choosing to feed for a shorter time; it depends on the individual circumstances of the sponsoring agency.

In Bexar County, there has been a 17 percent drop in the number of sites open in August since 2013. Most of that loss occurred between 2013 and 2014, when the Society of St. Vincent de Paul of the Arch Dioceses of San Antonio, a charitable catholic organization, stopped participating in the federal programs. The organization sponsored 62 sites in 2013.

Possibly. August has always been a hungry time for children in Texas. Most programs peak in June. Starting in July, programs start closing their doors en masse, and by August there are far fewer sites serving.

In June, there are 406 sites and 361 are open to any child. On Aug. 1, only 217 open sites are serving. As of Monday (Aug. 7), with San Antonio Independent School District students scheduled to return to school next week, only 103 sites still served.

Most students in Bexar County go back to school Aug. 21. For them, the week of Aug. 14 will likely be the hungriest week of the year, with only 57 open sites within the roughly 1,256 square miles of Bexar County.

For most districts, the summer food program is a fiscal juggling act.

In Texas, sites that receive reimbursement must be in operation for 30 days — but they do not have to serve on each of those days. For example, a site could open in the beginning of June and serve food every Monday and Wednesday until it closed in the beginning of July. It would have operated over a period of 30 days, even if it actually only served 6-8 days.

Each organization has the power to decide what days it will serve and when it will operate.

With each meal reimbursement, small reimbursement covers overhead cost like facilities and staff. The amount of the reimbursement varies based on several factors, but it’s not a lot of money per meal.

If the reimbursement rate is 50 cents per lunch for overhead costs, then a site that costs $300 a day to operate would have to serve 600 meals daily to break even.

It’s a little more complicated than that, but the bottom line is that program sponsors have to make tough decisions about where and when to serve so that they are breaking even.

Districts like SAISD break even by carefully selecting what sites to serve and when, said Jenny Arredondo, the senior executive director of Child Nutrition Services.

Other districts, like Harlandale ISD, do not break even. The district has been in the red the prior two summers. Marcos Rodriguez, director of child nutrition at Harlandale ISD, has worked to change that this summer by offering the same meals more frequently, so there is not product waste if a site supervisor orders too much of a meal item like pasta.

On average, in 2016 in Bexar County, district sponsored sites served food for 14 days. All other sites averaged 18 days.

There are several reasons.

To qualify for federal reimbursement, sites have to be located in an area where 50 percent or more of the students are considered economically disadvantaged.

Four Bexar County school districts, including Alamo Heights ISD and Lackland ISD, do not qualify to serve. Four additional districts that are partly in Bexar County, including Comal ISD and Medina Valley ISD, also do not qualify.

These districts are home to pockets of hunger for needy children. These children would have to cross into another district to receive food, which is unlikely for many given the challenges of travel (see map above).

It is hard for nonprofits to serve these areas because they have to prove that there is need — something they normally do by referencing the percentage of economically distressed children at the nearest school. If the school doesn’t qualify, then they have to use census data to show there is still a need.

In large districts, the sites that serve might be concentrated in one high-need area, leaving other parts of the district barren.

(Note: Children can go to any open site in the U.S. to eat. If there are 20 hungry children in a district, and only two meals served per day, that is not a guarantee that 18 children are not eating. They could be crossing into another district, or even be living out of state for the summer. Those two children that are being served could be from out of state, or might not be considered economically distressed. It is impossible to prove exactly what children are eating and from where they are receiving the food.)

Rural and large districts

East Central ISD and other large or rural districts struggle the most to serve hungry children, according to our analysis.

East Central ISD is a rural district with a low concentration of students. The district covers 265 square miles and only sets up two feeding sites. Many children commute 20 minutes to the nearest school during the academic year. Ashley Chohlis, ECISD’s director of leadership development and administrative services, said that often parents don’t have the gas money to transport their kids to the nearest site in the summer, especially if the campus closest to them is not serving.

The transportation department provides pick up and drop off locations for parents who want their children to eat at one of the sites, but for many children the stops are still far from their homes and often at the end of rural roads with no sidewalks or overgrown grass.

North East ISD has a relatively successful program, but it still struggles to reach more children, especially in harder-to-access areas.

“There are so many barriers for participation in the program,” Sharon Glosson, North East ISD’s executive director of school nutrition, said. “We can be there. We can have food. It’s free. We can do all these things, but there may be barriers we are never able to address, like safety and security. If the child’s parents are at work and the kids have been told ‘you don’t leave the house’ — they can see us out the window with the meals, yet they can’t access them.”

Transportation

Even small districts like Harlandale ISD — only 14 square miles with many sites spread throughout the district — report that students have trouble reaching sites.

Most parents work — many two jobs — and they are unable to take the children to the sites. Several directors of school and nonprofit sites said many of the children they are trying to serve cannot leave their houses because their parents have left them home alone to go to work. Even if a parent could take them to breakfast, they wouldn’t be able to pick them up, return them for lunch, and pick them up again.

Districts that have started offering programs during the summer, so that children can stay on campus all day, have had higher turnout rates. This summer, both Harlandale ISD and East Central ISD received money — from separate, independent agencies — to run camps. Both districts expected to see a higher rate of children being served this summer.

Rachel Cooper, senior analysis with the Center for Public Policy Priorities (CPPP), explains that summer is already more expensive for parents because of the higher cost for electricity, gas and child care. For parents who cannot afford lunch during the school year even without these increased costs, it is not practical for them to pick up the extra cost in the summer.

It is often harder for nonprofits to reach students than it is for schools.

School districts have established sites throughout the entire area they serve. Each summer, nonprofits must identify the areas in need and establish sites. They also cannot provide transportation to the sites, like some school districts do.

Many nonprofits lack the infrastructure to pull off a summer food program. “One of the difficulties is that if you are a nonprofit you have to spend all this time ramping up to serve for this short period of time, then you have to spend all this time tearing down,” Rachel Cooper said.

The Food Bank hired 35 seasonal employees and leased 13 vehicles to meet the additional need this year. During the school year, the Food Bank serves an average of 1,500 meals per day. During the summer, the number climbs to 5,000.

District-sponsored sites served 321,964 lunches from 150 sites last summer. All other sites served 299,354 lunches from 230 sties. So nonprofits are operating more sites while serving fewer children.

Note that not all nonprofits receive funding through the federal government. Programs like Snack Pak 4 Kids raise their money independently, so their numbers would not be included in this data.

Advocacy groups like FRAC and CPPP would like to see participation in the summer programs increase.

Advocates have suggested lowering the economic qualification for federal reimbursement from 50 percent to 40 percent — meaning sites that were 40 percent economically disadvantaged would qualify to serve, instead of the current limit which is 50 percent — but that could cost hundreds of millions of dollars, Rachel Cooper said.

Next year, Texas will participate in a pilot program that will give needy families additional help from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), so that they will not have to travel to sites for food. This program would likely cost billions to roll out nationwide, Rachel Cooper said.

In the meantime, many nonprofits and districts continue to forge ahead with innovative ways to get food to children, including mobile cafes. These solutions are not permanent ones, but they are part of the patchwork of resources that schools, families and nonprofits cobble together to help children make it through the summer.

Part 2 will look at a how some San Antonians are taking the fight against summer on the road.

This article was originally published by the H.E. Butt Foundation’s Folo Media initiative in 2017.